Contents of Article

- What is strength training?

- What are the principles of strength training?

- What are the benefits of strength training?

- Misconceptions of strength training

- How often should you strength train?

- Common strength training equipment

- Strength training vs cardio

- Does strength training burn calories?

- Strength training examples

- Conclusion

- References

What is Strength Training?

The term strength, or strength training, is often used interchangeably with resistance training or resistance exercises. Strength or muscular strength is defined as the ability to generate maximum external force. (1) An internal force would constitute part of the human body applying force on another part whereas external forces pertain to an environmental force against the human body. Therefore, for this article, the definition of strength relates purely to how the human body can exert force against an external factor. Other definitions relating to strength describe it as the ability to contribute to maximal human efforts in sport and physical activity (2). Regardless of the exact definition used, strength is fundamental to a human being outside of the realm of just sports performance context. Joyce and Lewindon (2014) go on to further define maximal strength as the ability to apply maximal levels of force or strength irrespective of time constraints and relative strength is the ability to apply high levels of force relative to the athlete’s body mass (3).

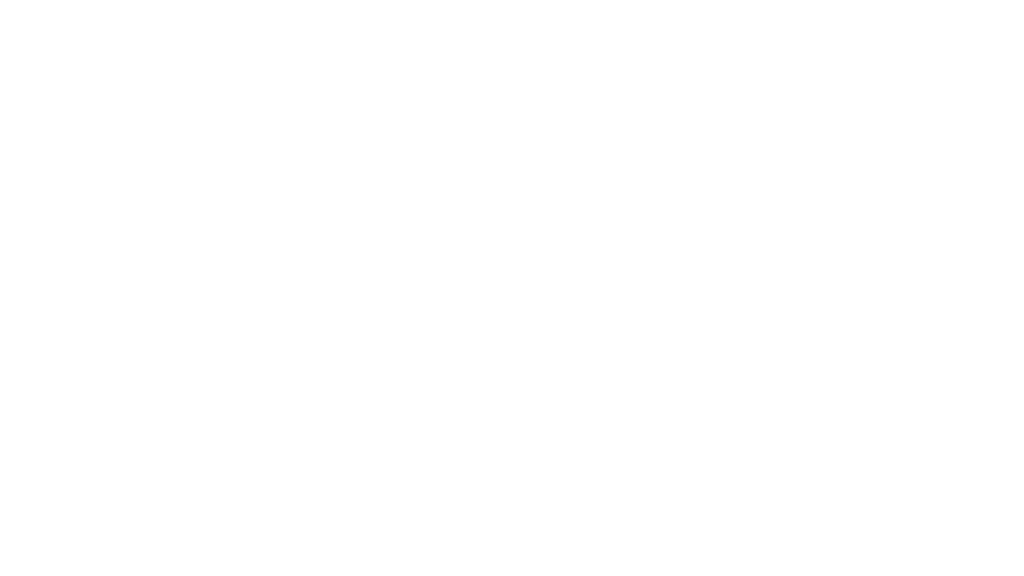

Strength can be distinguished based on three muscle actions: concentric, isometric, and eccentric contractions. Concentric actions refer to the muscle shortening, and normally maximal strength is measured concentrically before an eccentric movement occurs. Eccentric action is the opposite of concentric in that a muscle creates less tension and lengthens. Isometric contractions almost sit in between concentric and eccentric in that they create tension without shortening or lengthening (4).

Figure 1 shows an example of the bicep muscle and how each part of a bicep curl will pertain to the type of action being used. As the individual curls the weight towards their body, they are moving it concentrically where the bicep muscle is shortening. As soon as the weight starts to move away from the body, the bicep muscle is lengthening and therefore is the eccentric part of the exercise.

Figure 1. – Muscle can actively exert force regardless of whether the muscle gets shorter, stays the same length, or gets longer due to the opposing force (20).

Strength can often be termed as ‘absolute strength’ or ‘relative strength’. Absolute strength pertains to an athlete’s capacity to exert maximum force regardless of what their body weight is (4), whereas relative strength considers the body weight of an individual and therefore is a ratio of the two. Some sports are divided into various weight categories such as boxing or gymnastics, in which case a high level of relative strength is imperative.

Finally, general strength training looks at the foundation as an entirety of improving the strength of the entire body. Low general strength levels may indicate or lead to injury or a higher susceptibility of it, or asymmetrical issues and imbalances. Specific strength training takes a more sport-specific approach so athletes can be strong in certain planes, ranges of motions or movements based on the demands of the sport (4).

What are the principles of strength training?

Constructing a strength plan and goals requires us to understand the basic principles to make sure we are getting the biggest bang for our buck. The same goes for aerobic training, these foundational principles are specificity, overload, and progression.

Specificity is a basic concept where an individual is to train in a specific manner to produce a specific response or action. In practical terms, if someone wanted to design a program around strengthening their hamstring muscles, they would have specific exercises to match the required demands. Exercises that could occur in this scenario may be the deadlift, glute bridges, or Nordic curls. In an athlete’s sense, specificity can relate directly to the sport by mimicking movement patterns or becoming a supplementary addition to improve strength levels that can transition to the pitch and aim to enhance performance.

Overload is about assigning training or sessions of greater intensity than the athlete is accustomed to. Without the stimulus overload, even a well-designed program will limit the athlete’s ability to seek improvement (2). An example of progressive overload can be changing the load a person is lifting to make it harder or adding in more strength days per week. Another manipulation could be made by adding more exercises to the session or tweaking the rest periods in between. Finding the balance between overloading and not overtraining is vital. If a program is correctly designed, it will challenge the individual enough to enhance strength improvements but consider required recovery/rest days.

Progression has a methodical approach to prevent potential overuse or injury from occurring. It may seem like you can make a big leap by lifting a heavy load one week compared to the last, but jumping straight into it without a designated plan can have many disadvantages, with injury being at the forefront. Lifting heavy loads will provide an important overload, but not at the expense of sacrificing proper technique and form. Progression should, when applied correctly promote long-term training benefits (2).

What are the Benefits of Strength Training?

Strength training provides a wide range of benefits to individuals regardless of age or experience level. It has been shown to increase muscle size and strength, help stabilise joints and ligaments, improve neurological signalling, aid in power mechanism and speed as well as many studies detailing the importance it can provide for mental health. Research has shown that doing strength training can reduce symptoms of various chronic diseases like arthritis, depression, type-2 diabetes, osteoporosis, sleep disorders and heart disease. In addition, some research demonstrates that strength training in older adults with functional limitations can reduce falls (5, 6). A long-term study conducted by Nelson et al. noted that women aged 50-70 years old who participated in strength training twice a week for one year became stronger, increased their muscle mass, improved their balance, and reported better bone density in comparison to the control group who did no strength training at all (6).

Misconceptions of Strength Training?

A few studies have investigated the preconception of strength training about males’ and females’ perceived importance of it. A common belief today is that many females have a negative preconception of strength training for multiple reasons. Some believe that by engaging in strength training they will add a lot of muscle mass and become aesthetically bigger, while others believe that is it not necessarily important for them to participate in whether they are an athlete or not. Poiss et al (2004) surveyed this exact issue at the collegiate level by exploring the perceived rates of the importance of strength training and found that male athletes were found to be significantly more likely to consider weight training as essential to their sport-specific training than females (8). Similarly, Bennie et al (2020) completed a comprehensive study, spanning 28 countries in Europe and found that 19.8% of men participated in strength training activities ≥2 times a week compared with 15% of women (9).

A common misconception is that cardio-based training is the best and only way to lose weight or specifically, body fat percentage, and strength training does not do this. Excessive body fat can be associated with a major risk for general health and can lead to life-threatening conditions or diseases. Several studies (11, 12, 13) have found that increasing resistance or strength training can positively affect body fat percentage alongside managing obesity or metabolic disorders (12). In line with these findings, a study that compared endurance to strength training over 10 weeks in male physically active participants, concluded that although resistance training alone may improve muscular strength and basal metabolic rate (BMR), and endurance training alone will increase aerobic power and decrease body fat percentage, a combined approach is optimal (10).

NB! An important thing to note is that muscle has a higher density than fat. If an individual implements strength training into their routine they could find an increase in weight (kg) however their fat stores have decreased, leading to reduced limb circumference and a change in body composition. Checking body fat percentage is a better metric that a person may look to improve. To summarise, a bodybuilder and an individual with obesity could have the same BMI, but the bodybuilder would have a higher percentage of muscle mass than the individual with obesity, who will have a greater percentage of body fat.

How often should you strength train?

The amount of strength training required will depend ultimately on the goals. An athlete looking to focus on maximising strength to translate to their sport will have different goals compared to an athlete or individual who is returning from a serious injury and focusing on regaining baseline strength. An elderly person looking to keep a good foundation of strength to help with functional movement will have different goals than a bodybuilder looking to enhance hypertrophy. These different scenarios will elicit a different training need and therefore frequency, duration, and load needed.

Various research alludes to differences in the frequency of strength training that should take place each week. Outside of sports performance, literature and article results can fluctuate from anywhere between 1-4 sessions per week as a general recommendation. Many studies will look at untrained, non-elite or recreational adults who engage in resistance training and often conclude direct strength improvements. In terms of experienced lifters, Lasevicius et al (2019) examined the difference in resistance-trained men by comparing 2 sessions a week to 3 sessions to determine if any significant differences were noted. The study concluded that although a significant difference was found between pre and post-test scores, there were no differences between the two groups and despite 2 or 3 training days per week, they both evoked similar responses (18). Contrastingly, other studies have found differences between groups when comparing 3 strength sessions a week to 6 sessions concerning the training volume per session (19). What does this mean? There is no exact science with how much strength training you should do as it will elicit various physiological responses for individuals at different time points. Strength training provides major benefits to health, so just getting started and remembering individualisation is key.

Strength Training for Athletes

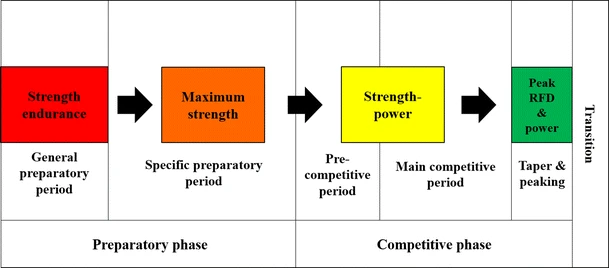

There are multiple ways that strength training can be programmed, often, athletes will fall into a periodization model where it considers their competition fixtures throughout the season and looks to maximise strength at the right time. There are multiple tactics to do this, but with periodisation, a coach can manipulate loads based on the goals within a set cycle. An annual plan is usually put together at the start of a new season which incorporates the macro-cycle which is essentially looking at the bigger picture. What games are there, and how long is the pre-season, in-season, and off-season period in terms of weeks. Within the macrocycle, this is then broken down into a meso-cycle and then finally a micro-cycle. The micro-cycle is a short time that could equate to a week as an example, which provides details of how the exact strength sessions may look in terms of exercises, reps, sets etc. The meso-cycle sits in between both which looks at when strength training sessions may be added throughout the month with a potential focus attached to it.

Figure 2. shows an example that Suchomel et al (2018) documented on periodisation with the various stages. The preparatory phase is typically the off-season where maximal strength can be focused on then as pre-season begins this will start to transition to strength-power training. During the season most sports will strip back on strength and replace it with technical or tactical training. Strength-power is imperative for the athletes to complete during the main season to keep them strong and ticking over. The only difference is the load may be reduced and the session will be scheduled by the S&C team to promote enough recovery time before competitive games to avoid a decrease in performance.

Figure 2. An example of strength focuses during the preparatory and competitive phase (7).

Common Strength Training Equipment

Strength training can be completed with various equipment or methods to stimulate a similar response. Examples include free weights, body weight movements, machines, and/or resistance/elastic bands.

Bodyweight exercises

For a beginner, body-weight exercises are a great way to learn different movements and perfect form. A completely new beginner will likely find adaption through body-weight exercises as they have several advantages as noted above in the benefits of strength training. Not only do they target various muscle groups but there is the potential for lots of versatility. A plateau can occur when using strictly body weight exercises as an overload of a stimulus is limited in nature so other strength training methods are often added or advised to seek further improvement (6). These exercises or movements are great for people returning from injury or starting an activity for the first time. It is the foundation or building blocks to get people moving correctly before adding additional load.

Free Weights

Dumbbells, kettlebells, or barbells can be used as free weights and as the name suggests, they are not attached to a machine. There are many advantages to using free weights and lots of exercises that can be progressed or regressed as necessary with them too. One main advantage is that by using free weights they force stabilisation, range of motion, and coordination. A back squat for example using a barbell will require a person to work their quadriceps in the concentric movement but they need to engage other muscles and the core to create the movement to be as efficient and smooth as possible. With free weights, an element of balance is needed so alongside strength gains these types of exercises can help improve balance and coordination as well.

Machines

Many different machines can be found in a gym setting that looks to isolate specific sets of muscle(s). For a beginner, machine exercises may be a great place to start as they are often user-friendly, and less technique is required in comparison to free weights. They provide isolated work and load to a specific area of the body which means any discrepancies or imbalances could be addressed by adding in machine movement. If imbalances are a problem, machines can become a potential hindrance if one muscle group or one side dominates or takes most of the force. For example, a leg press machine requires both feet to push against the resistance. If an individual has an obvious stronger side, they may find that one leg is working harder than the other, therefore, taking most of the weight. A recommendation would be to assess any potential imbalances or discrepancies an individual or athlete has before assigning a program as exercise selection can be manipulated. Machines could still be used if other exercises address the imbalances that were found. Often, a machine has less risk of getting the movement wrong and can move the body through the desired range of motion.

Read this article to find out more about free weights vs machines.

Resistance Bands

Resistance bands can be used to create tension or make movements more difficult as the muscles work to resist the pressure created. Resistance bands can come in all shapes and sizes with the strength of the band getting thicker which ultimately means it is harder to resist. Beginners can use bands as a good starting point and work their way up to harder bands as they become used to the tension. They are a great way for injured athletes to build up strength after rehabilitating from a knee ligament injury (14). One disadvantage to using resistance bands is it is hard to evoke the same resistance each time as it is purely subjective.

Strength Training vs Cardio

On a basic level, strength and cardio training play different roles, and have an obvious difference in that cardio training aims to improve oxygen efficiency whereas strength training adds stress to the muscle to gain strength. Going for a steady state long run versus completing heavy weight lifts in the gym will provoke different energy pathway responses.

Our energy pathways will work together but depending on the activity we are doing, will depend on which energy system is working as the predominant source. Maximal strength, often, is where minimum reps are conducted but the load is extremely high. An example of this may be an athlete completing a 1 repetition maximum (RM) – 3 RM bench press. It is an intense few seconds of work where the body is heavily relying on the adenosine triphosphate-phosphocreatine (ATP-PCr) system to provide a high capacity of power through the stored ATP and PCr we have but it will only last a few seconds. Once this energy has been used, our body will then upregulate the anaerobic glycolysis which provides more energy, still at a high-power outlet, but not the same as the ATP-PCr. The benefit to the anaerobic glycolysis is the duration can be longer which will certainly help when we look to do strength training where it lasts more than a few seconds. In terms of cardio-based training, again, it will depend on the intensity and duration of the task to what energy system is in the driving seat. If a person were to do a long steady state run at the same speed, they would be utilising their aerobic capacity system as their predominant energy system. This will allow an individual to be able to work for a long period at a relatively low intensity. Even by utilising anaerobic energy pathway, we often rely on strong aerobic power for a quick recovery and regeneration between actions (15)

Does Strength Training Burn Calories?

Having already established that strength training can have profound effects on an individual’s health it is important to note how strength training can and does burn calories. It is often associated that aerobic-based activities are the most effective for burning calories and improving cardiovascular fitness. By participating in regular muscle-building activities, the muscles are metabolically active and will therefore burn calories (16). Muscles require a lot of calories to function even at rest and strength training requires substantially more calories. With regular strength training, muscle mass will increase which increases your metabolism and therefore can lead to burning more calories at rest and throughout the day (17).

Strength Training Examples.

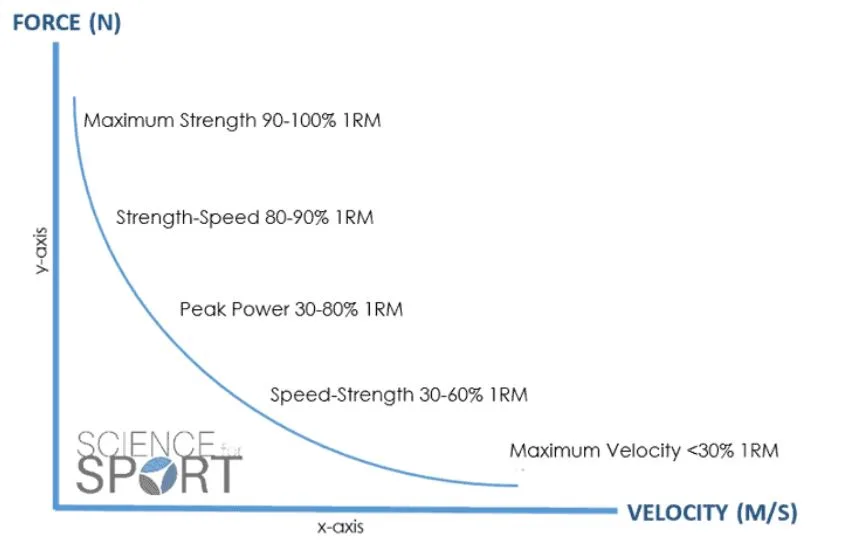

Strength training sessions will differ depending on your desired goal or outcome. The force-velocity curve in Figure 3 is based on your 1RM and the percentage you are working at. Working at the top of the y-axis shows that the weight is very heavy and maximal strength is the main goal whereas the furthest point along the x-axis has no more than 30% of your 1RM where you are focused on moving it quicker, but the load of course is lighter.

Figure 3. Force Velocity Curve.

A strength session can be a total body focus which encompasses movements accommodating a variety of muscle groups from both upper and lower. Some like to do a split, where they complete an upper-body session one day and a lower-body session the next. Another well-known spilt is something called the ‘push and pull’. An example of a push exercise is where the movement or weight is being pushed away from the body, such as a bench press, push-up, shoulder press or overhead press. As the word ‘pull’ insinuates the body is contracting muscles and pulling a force towards the body. Examples of a pull exercise could be pull-ups, lat pull down, bent-over rows or a deadlift. An example for a beginner is represented in Table 1 and specifically for a female football athlete in Table 2. These are noted as generic examples of how a strength session could look, but individuality must be considered when designing a programme to suit the needs, goals and preferences of the individual.

Table 1. An example of a total body strength session for a beginner.

Exercise | Reps | Sets | Load | Rest |

| TRX Squat | 12-15 | 3 | BW | 2-3 mins |

| Hamstring Curl with Stability Ball | 12-15 | 3 | BW | 2-3 mins |

| Lat Pull Down Machine | 12-15 | 3 | Relevant to reps* | 2-3 mins |

| Push ups | 12-15 | 3 | BW | 2-3 mins |

| Bicep Curls | 12-15 | 3 | Relevant to reps* | 2-3 mins |

| Triceps Cable Pull down Machine | 12-15 | 3 | Relevant to reps* | 2-3 mins |

*The individual will need to have a play around with a weight that they know they can get to around 12-15 reps but does not inhibit them reaching the desired amount, or it is not easy enough they can progress over 15 reps.

Table 2. An example of a total body strength session for a female football athlete in the off-season during the summertime.

Exercise | Reps | Sets | Load | Rest |

| Barbell Back Squat | 8-12 | 3 | 75 % | 2-3 mins |

| Barbell Romanian Deadlifts | 8-12 | 3 | 75 % | 2-3 mins |

| 3D Barbell Lateral Lunge – Emphasise quickness over range | 10 each leg | 3 | < 25 kg | 2-3 mins |

| Dumbbell Bench Press | 8-12 | 3 | 75 % | 2-3 mins |

| Double Arm Cable Row | 8-12 | 3 | 75 % | 2-3 mins |

| Front Plank | 60 secs | 3 | BW | 30 secs |

| Side Plank | 60 secs | 3 | BW | 30 secs |

| Deadbugs | 12 each side | 3 | BW | 30 secs |

As an athlete, coach or practitioner interested in more specific elite athlete training, check out the article on training methods of elite-athletes.

Conclusion

Strength usually refers to our ability to resist an external force and much literature urges the importance of regular strength training. It has been shown to increase muscle mass, provide stability to ligaments and joints, develop stronger bones, and help reduce the potential of various illnesses and diseases. There are multiple ways to engage in strength training exercises through machines, free weights, resistance bands or bodyweight movements. Strength training is imperative for everyone, not just athletes, and will help enhance overall quality of life with a regular structured routine.

- Zatsiorsky. V.M., Kraemer, W.J., Fry, A.C. (2021) ‘Science and Practice of Strength Training’, Human Kinetics, Third edition, pp.3-60. [Link]

- Baechle, T.R., Earle, R.W. (2008) ‘Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning’, Human Kinetics, Third edition. [Link]

- Joyce, D., Lewindon, D. (2014) ‘High-Performance Training for Sports’, Human Kinetics. [Link]

- Bompa, T., Buzzichelli, C., A. (2015) ‘Periodization Training for Sports’ Third edition. [Link]

- Seguin, R., Nelson, M.E. (2003) ‘The Benefits of Strength Training for Older Adults’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25(3), pp.141-149. [Link]

- Nelson, E., Fiatrone, M., Morganti, C., Trice, I., Greenberg, R., Evans, W. (1994) ‘Effects of High Intensity Strength Training on Multiple Risk Factors for Osteoporotic Fractures’, JAMA, 272, pp.1909-14. [Link]

- Suchomel, T.J., Nimphius, S., Bellon, C.R., Stone, M.H. (2018) ‘The Importance of Muscular Strength: Training Considerations’, Sports Med, 48, pp. 765-785. [Link]

- Poiss, C.C., Sullivan, P.A., Paup, D.C., Westerman, B.J. (2004) ‘Perceived Importance of Weight Training to Selected NCAA D3 Men and Women Student Athletes’, Journal of Strength and Conditioning, 18(1), pp.108-114. [Link]

- Bennie, J.A., De Cocker, K., Smith, J.J., Wiesner, G.H. (2020) ‘The Epidemiology of Muscle Strengthening Exercise in Europe: A 28-Country Comparison Including 280,605 Adults’, PLoS One, 15. [Link]

- Dolezal, B.A., Potteiger, J. (1998) ‘Concurrent Resistance and Endurance Training Influence on BMR in Non-Dieting Individuals’, Journal of Applied Physiology, 85(2), pp.695-700. [Link]

- Westcott, W.L. (2012) ‘Resistence Training is Medicine – Effects of Strength Training on Health’, Current Sports Medicine Reports, 11(4), pp.209-216. [Link]

- Strasser, B., Schobersberger, W. (2011) ‘Evidence of Resistance Training as a Treatment Therapy in Obesity’ J. Obesity, 2011. 482564. [Link]

- Campbell, W.W., Crim, M.C., Young, V.R., Evans, W.J. (1994) ‘Increased Energy Requirements and Changes in Body Composition with Resistance Training in Older Adults’, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 60(2), pp.167-75. [Link]

- Mavrovouniotis, A., Potoupnis, M., Sayegh, F., Galanis, N., Argiriadou, E., Mavrovouniotis, F. ‘The Effects of Exercise on the Rehabilitation of Knee Ligament Injuries in Athletes’, European Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science, 5(12), 3382261. [Link]

- Bogdanis, G.C., et al. (1996). ‘Contribution of Phosphocreatine and Aerobic Metabolism to Energy Supply During Repeated Sprint Exercise’, Journal of Applied Physiology, 80, pp.876-84. [Link]

- Brown, L.E. (1956). ‘Strength Training’, Second Edition, Human Kinetics. [Link]

- Incledon, L. (2005). ‘Strength Training for Women’, First Edition, Human Kinetics. [Link]

- McLester, J.R., Bishop, P., Guilliams, M.E. (2000). ‘Comparison of 1 Day and 3 Days Per Week Equal-Volume Resistance Training in Experienced Subjects’, J Strength Cond Research, 14(3), pp.273-281. [Link]

- Colquhoun, R.J., Gai, C.M, Aguilar, D., Bove, D., Dolan, J., Vargas, A., Couvillion, K., Jenkins, N.D.M., Campbell, B.I. (2018). ‘Training Volume, Not Frequency, Indictive of Maximal Strength Adaptations to Resistance Training’, J Strength Cond, 32, pp.1207-1213. [Link]

- Chedrese, P.J. and Schott, D. Communication systems in the animal body. University of Saskatchewan. [Link]