Contents of Article

- Summary

- History of Women’s Football

- Needs Analysis of the Female Footballer

- Considerations for Women’s Football

- Data Analysis in Women’s Football

- Performance Testing in Women’s Football

- Program Design Ideas for Women Footballers

- Conclusion

- References

Summary

The demands of women’s football are ever-evolving. Like all sports, it is a process of identifying the key physiological metrics and demands that are placed on the athletes to further enhance performance across various levels.

History of Women’s Football

For 50 years, women were banned from playing football. During the first world war, the men would have fulfilled their duties of fighting in the war, while the women stayed at home to reoccupy the roles that were left, working in factories, and assisting to raise funds for the war efforts. During this time, women took up playing football in more organized games and events with an estimated 150 teams created across the country.

After the First World War, the men’s leagues which were previously suspended, resumed, despite women’s football being at an all-time high where a match on Boxing Day drew in a crowd of 53,000 people. In 1921 the English FA decided to ban women’s football quoting it to be, ‘quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged’. The ban was later lifted in 1971, ending a 50-year absence of women’s football. (1)

Women’s football is now at an all-time high with more global exposure, greater access, and massive demand for more resources at both elite and non-elite levels. Just six days into the FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023 a record high of 1.5 million tickets were sold (2). Coming off a historical UEFA Euros campaign for the Lionesses, it was more than just bringing home a trophy – it was creating a lasting legacy.

Looking to the future, the Lionesses wasted no time in creating a UEFA-supported legacy programme to get more females into football consistently. The history of the game is pivotal in understanding the demands as it has changed and will continue to change through time.

Needs Analysis of the Female Footballer

It is imperative as a practitioner to complete a thorough Needs Analysis to not only identify the demands an athlete has placed upon them in a game scenario but to inform the training strategies while aiming to minimize any potential injury threat.

Focusing on strictly women’s football, Turner and colleagues (2017) produced an in-depth ‘Part 1 – Needs Analysis’ of the game looking at these key areas. A follow-up piece was created, noted as ‘Part 2 – Training Considerations and Recommendations’. This research is an important starting point to understand the key demands of the game.

In basic terms, during a game, a female footballer is likely to:

- Sprint

- Jog

- Walk

- Sideways or lateral shuffle

- Backwards running

- Jockey

- Jump

- Turn or change of direction

Energy Systems

The movements identified correspond with our energy systems depending on the demand placed on each activity listed, and the time and intensity those movements are completed for. In simple terms, the energy systems are broken into aerobic and anaerobic metabolism where oxygen is either present or not, respectively.

The anaerobic energy system is divided into alactic and lactic components, which ultimately refers to a process of spitting stored phosphagens, ATP and phosphocreatine (PCr), and the nonaerobic breakdown of carbohydrates to lactic acid through glycolysis (3). The aerobic system, also known as the oxidative system, requires oxygen to produce ATP and is the preferred system for long-duration and/or low-intensity activities. All three energy systems will be active during exercise or physical activity, but one will be working predominately harder or more consistently than the others. The key to which energy system is in the driving seat lies within the duration of the exercise being completed and the intensity of it.

For example, a marathon runner will utilize more aerobic capacity due to the long duration of the event, whereas a 100 m sprinter will maximize their anaerobic, also called the phosphagen system, as a quick burst of high-intensity maximal force is needed. The glycolytic system is further broken down into fast and slow glycolysis. Fast glycolysis refers to pyruvate being converted to lactate which is faster but is limited in duration, while slow glycolysis allows a longer duration but is when pyruvate is shuttled into the mitochondria to undergo the Krebs Cycle (4). In football, certain movements such as jumping, sprinting, or turning direction maximally will require the anaerobic energy system to kick in, but athletes need to last a 90-minute period which draws on the aerobic energy system capabilities.

“It is explosive actions such as sprinting, jumping, tackling and change of direction (COD) that seem to influence the outcome of games.” – Mujika et al., (2009).

Key Demands for Women’s Football

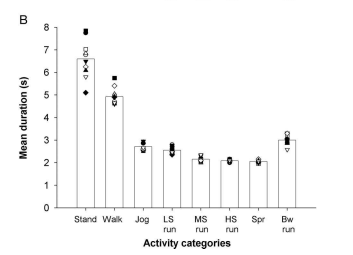

In a study by Krustrup and colleagues (2005), it was acknowledged that females spent 16% of their time standing, 44 % walking, 34 % on low-intensity activity and 4.8 % running at high intensity during a competitive match (5). Despite this study being completed over 15 years ago, some of the findings are still similar in the modern game concerning percentages around specific movements and time spent completing a given task.

The key demands we must consider for women’s football are:

- Aerobic Capacity – VO₂ Max

- Strength & Power

- Speed and Change of Direction

- High Intensity or High-Speed Running

Aerobic Capacity

Maximum oxygen uptake (VO₂ max) is defined as the greatest amount of oxygen that can be used at the cellular level for the entire body. It is often found to associate with an individual’s physical conditioning status and accepted use of measuring cardiovascular fitness (6). According to Iaia, Rampinini and Bangsbo (2009), aerobic energy production is highly taxed and accounts for more than 90% of total energy expenditure during a football match (7).

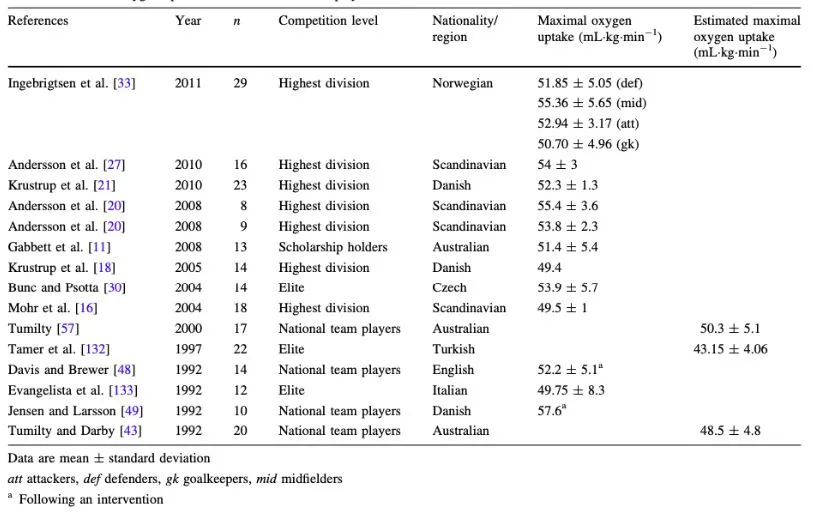

Certain metrics such as age, gender, fitness levels and elevation can affect the final VO₂ max score reading. Pertaining to female football players, it has been reported that an elite player will report a VO₂ max score of 49.4 – 57.6 ml⋅kg⋅min-1 (8). In perspective, the highest VO₂ max recorded to date is from cyclist, Oskar Svendsen, with a score of 97.5 ml⋅kg⋅min-1 and long-distance runner, Joan Benoit, with a score of 78.6 ml⋅kg⋅min-1.

Table 1. shows a representation of VO₂ max scores for elite, highest division, and national team female soccer players. Similarly, to research conducted by Datson and colleagues (2014), all scores reflect the same metrics identified that an elite female soccer player needs to show to compete at the highest level.

Speed and Change of Direction

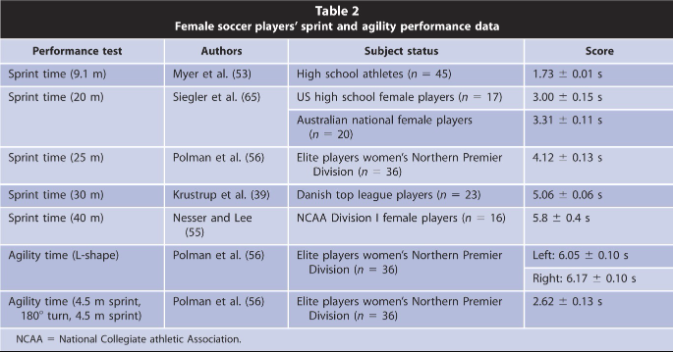

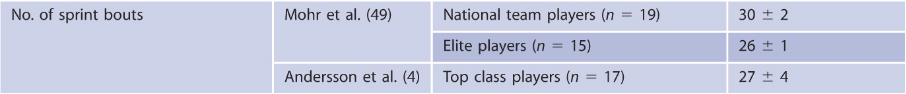

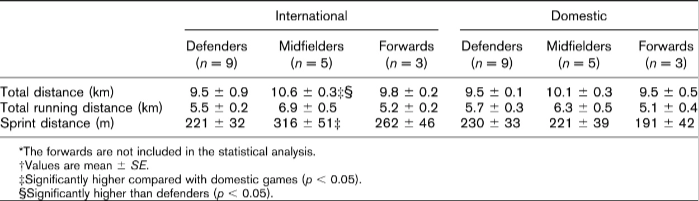

Speed is movement distance per unit of time and is often quantified as the time taken to cover a fixed distance (9). Figure 3 represents normative data reflecting different linear sprint times across various distances and levels for female soccer players. While Figure 4 pinpoints the number of sprint bouts that players racked up during a match. This normative data allows those specific teams to inform training demands to mimic the average sprints per game, or, if in pre-season to increase the load to entice a progressive adaptation.

Table 2. Female soccer player’s sprint and agility performance as noted by Turner, Munro & Comfort (2020).

Table 3. Female soccer player’s sprint performance as noted by Turner, Munro & Comfort (2020).

Agility is defined as the skills and abilities needed to explosively change movement velocities or modes (9). Often agility and change of direction coexists as one but agility explicitly refers to changing direction because of a stimulus and thus change of direction, simply being a pre-planned movement ahead of time. The terminology surrounding these words is important as a practitioner as in a competitive environment female soccer players will be continuously responding and reacting to a stimulus (players, ball etc.) which relates to agility-based movements. According to Bangso (1994), players perform a different action every 4-6 seconds throughout a match whereas Tuner, Munro & Comfort (2013) define it as 1,300 changes in each activity during a match setting, which equates to a change every 4 seconds.

High-Intensity Running

High-intensity running, otherwise known as high-speed running, is the capability of athletes or players to perform short-duration sprints (< 10 seconds), interspersed with brief recoveries (< 60 seconds) (11). Elite-level athletes are typically able to clock up increased high-intensity runs per game, as well as distance, than non-elite athletes. Figure 5 represents normative data that can be used at the elite standard as a benchmark.

Table 4. Turner, Munro & Comfort (2020) research findings show the number of high-intensity runs that occurred as well as the distance (km).

Strength and Power

Strength is the ability to exert force (N) to overcome resistance while power is defined as the ability to exert force in the shortest time (Power = Force (N) x Velocity (m/s)) (9). Strength and power movements are often imitated in football during tackles, jumping, heading, and diving. Referring to the energy systems, these movements are more anaerobic based due to the nature of explosive strength or power needed for a small duration of time.

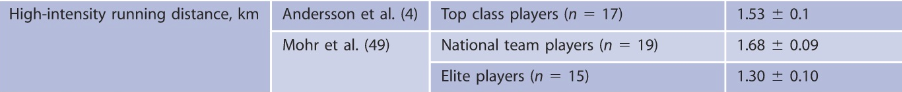

Table 5. A systematic review conducted by Datson et al. (2014) referencing various studies that completed the squat jump, countermovement jumps and drop jumps with their athletes.

In normative data terms, often a 1RM test can be used to gauge strength levels, but often teams are looking at the Countermovement Jump as shown in the data presented in Figure 6.

Considerations in Women’s Football

When working in women’s football some obvious, yet important, considerations that must be acknowledged are:

- Tactics

- Elite vs non-Elite

- Menstrual Cycle

- Injuries

Tactics

Every coach has a different philosophy and playing style which results in potentially different formations and tactics a player must understand. With different formations, a player’s role could change significantly, even if they are playing the same position. It is imperative that during the needs analysis, playing position is considered, as demands will naturally differ based on the role being played.

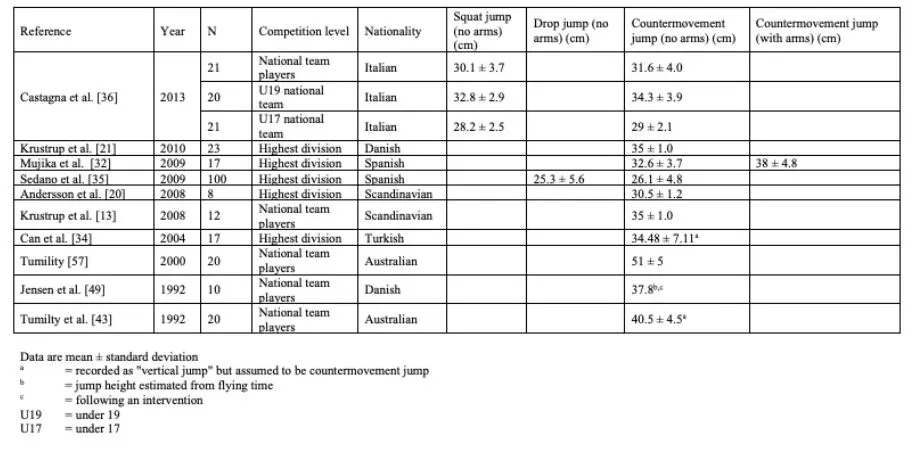

It is frequently perceived that midfielders will complete the most running and therefore distance in a match with defenders likely covering more lateral distance and strikers less total distance but more sprint bouts. International and domestic normative data is available as shown in Figure 7, where the work of Andersson et al. (2010), investigated the differences of players at club level and national level by playing position (12).

Table 6. Defenders, midfielders, and forwards data at international level and domestic.

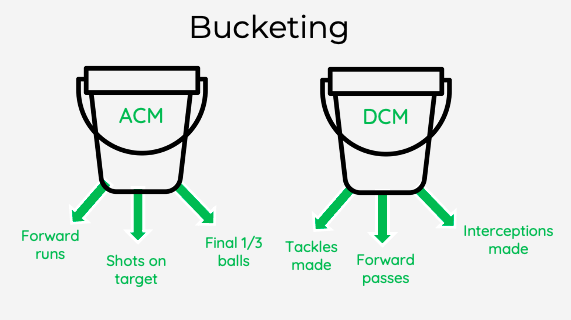

A great tool to assist with player observation and the objective data collected is to ‘bucket’ players. The process of bucketing players allows tactics to be taken into consideration while focusing on detailed metrics the players can meet, relative to their position. Figure 8 shows an example of how two similar positions on the pitch, can have different outcome measures based on what metrics or capabilities could be looked at. Bucketing works in multiple ways outside of data analysis, it can work for injuries, personality traits, fitness testing scores and numerous other areas a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) may wish to focus on.

Elite vs non-Elite

There is currently a huge gap in data between female athletes playing at an elite level, to those playing at non-elite. Non-elite teams often use their players as a normative data benchmark due to relevant research at the respective level just not being available or yet studied. Budgets, resources, training status and often quality is what separates the two. This is an important consideration to take into account as a coach or practitioner working at the non-elite level where players may have full-time commitments or work outside of training and game time. Being adaptable and keeping track of the player’s well-being must be at the forefront.

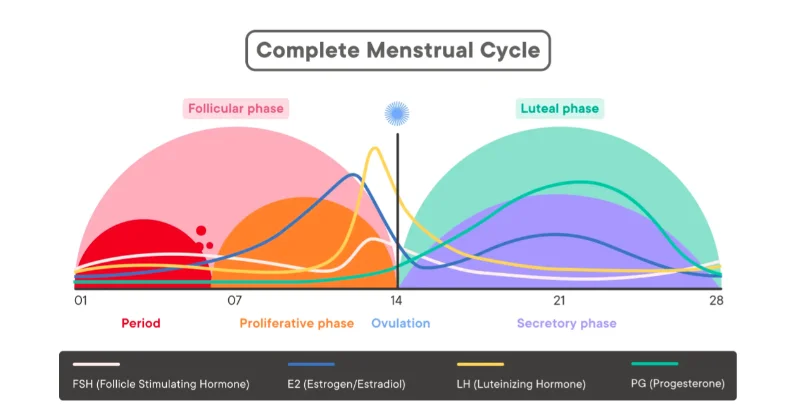

Menstrual Cycle

The menstrual cycle begins on the first day of menstruation which is when an athlete will be bleeding and persists until the start of the next period. A full cycle in academia is often referred to as 28 days, but this range can be anywhere between 21-35 days (13) and can vary from person to person. Each phase of the cycle should be treated as a separate hormonal profile, and the transition from one phase of the cycle to the next is complex, as the transition time is unclear, due to a lack of research within this area.

Not all female athletes will have a menstrual cycle, some may be taking prescriptive contraceptive pills which is a further consideration to think about. During the various phases, different hormone receptors will be adjusted and show altered levels pending the stage in the menstrual cycle. Pre-ovulation will show high levels of estrogen but significantly low levels of progesterone but as the luteal phase occurs these levels almost flip flop, where progesterone is at its highest and estrogen tails off.

Understanding the basis of the menstrual cycle will allow practitioners to work closely with their female athletes to best serve them, ultimately, keeping the athlete fit and healthy. The menstrual cycle must be treated as an individualized process as some athletes may suffer from heavy side effects, whereas some, may not report any during menstruation. A coach’s guide to the menstrual cycle assists with a more practical take away while a great resource to use is the Fitr Woman App, which provides detailed information and supports with tracking a menstrual cycle.

Injuries

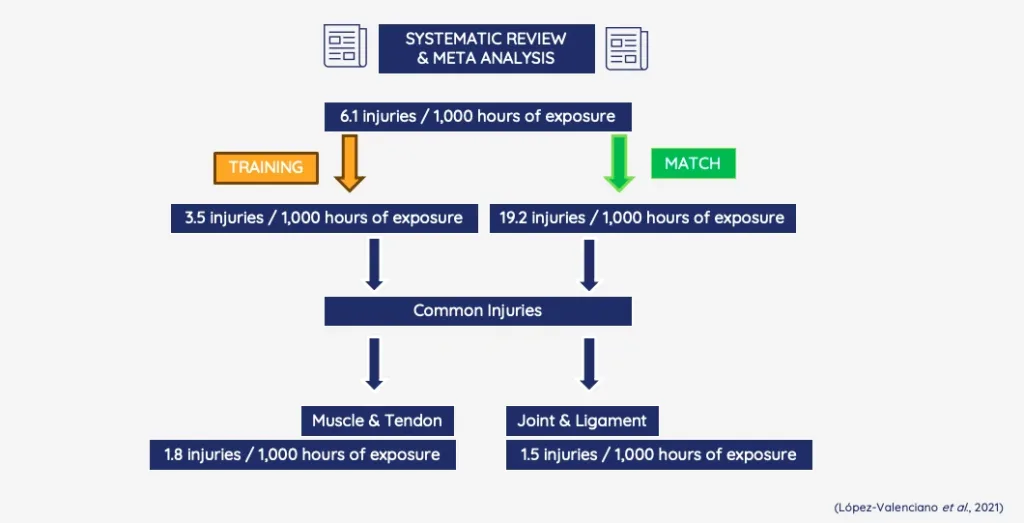

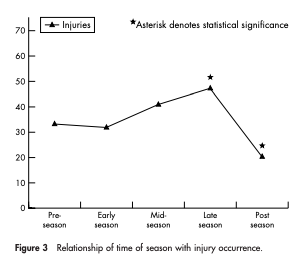

A recent study in 2021 conducted by López-Valenciano and associates (15), showed a systemic review and meta-analysis of the injury profile within women’s football (see Figure 10). The results concluded that injury rates were higher in a competitive match setting, where per 1,000 hours of exposure, 19.2 injuries were likely to occur (15). Within this, 1.5 injuries were related to joint and ligament per 1,000 hours of exposure while 1.8 injuries to muscle and tendon-based injuries. Figure 11 reflects on the seasonal calendar year where injuries are more common, and clearly notes, there is a vast significant difference between late in the season compared to post, pre- and mid-season. As practitioners, the duty of care in the mid-late stages of a season must be accounted for. Utilizing health and well-being regular check ins, alongside subjective and objective measures will avoid injury rates spiking.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) repeatedly takes the headlines when women’s football is discussed in terms of injuries and the rising occurrence rate happening across the top leagues worldwide. ACL injuries are multifaceted, there are multiple reasons why they may occur; anatomy and biomechanics, pitch surface, shoe type, menstrual cycle and hormones, player load, historical injuries, quad-to-hamstring ratio and simply, a contact tackle, or non-contact movement. Drawing on previously conducted literature, some quick snap figures are reported below:

72 % of ACL injuries occurred with non-contact mechanisms during sudden deceleration or landing manoeuvres (16). The rate of ACL injury occurrence in female athletes is higher in cutting, jumping, and pivoting sports compared with males (17). Female athletes were at nearly 4 times greater risk of injury than male athletes after having an ACL reconstruction surgery (18).

Data Analysis in Women’s Football

There are endless amounts of data points that can be collected and compared for an athlete or squad of players competing in competitive matches or training. The first step is to identify the global positioning system (GPS) in place and understand the terminology and data points being measured. Various companies will use different vocabulary, but often, relate to the same metric. Check out to data metrics measured below:

The ‘Rule of 3’

A top tip to allow data analysis to become more practical to best serve the athletes and build buy-in is focusing on 3 distinct areas and providing a rationale. A key example is noted below:

High-Speed Running

Why? High speed running can assist in the improvement of a player’s aerobic endurance to maintain a high level of performance. This metric is often the huge gap between elite and non-elite in terms of distance and time spent on high-speed running or high-intensity running.

Sprint Distance

Why? Twofold. Firstly, inform training sessions to maintain match fitness based on athletes ‘average or normal’ sprint distance in a game. This avoids overtraining which could lead to injury and undertraining which can lead to fitness levels not being realistic to match the demands. Secondly, provide a structure for subs or players who do not play > 30 minutes, additional support is used with objective markers to make player specific and relevant.

Accelerations and Deceleration Totals

Why? The MDT has reviewed injuries from the past season which reported a high number of athletes suffering from hamstring injuries (whether small, medium, or long in duration and recovery). Tracking Accels and Decels can assist in determining overall hamstring health in relation to sprint and movement form.

Before collecting any data it is crucial that you understand what GPS metrics you’d like to monitor and whether they are accurate or not. Data analysis requires buy-in from all MDT and players it touches and in this article, we explain how coaches and athletes can get the most out of GPS devices.

Fitness Testing in Women’s Football

Fitness testing, also referred to as performance testing, is vital to create club-wide normative data that can be used as a benchmark to push athletes to improve and ultimately, enhance overall performance. Working in a MDT is fundamental to ask the following performance testing questions: which tests? Why these tests? When do we test and re-test? A consideration for ease of transparency and application is to create buy-in from the players.

Possible aerobic capacity tests used to measure fitness levels for elite female footballers are:

- YoYo Intermittent Recovery Test 1

- YoYo Intermittent Recovery Test 2

- 1 Mile run

- 1.5 Mile run

- Maximal Aerobic Speed (MAS)

- The Man United Fitness Test

- The Cooper Run

- The Broncho Test

Agility tests that are often used could be, not limited to, one or more of the following:

- 5-0-5 Agility test

- Pro-Agility test

- T-Test

- Arrowhead test

- Illinois Agility test

- Zig Zag test

Sprint or speed tests often look to test an athlete’s maximal sprint across various distances such as 5 m, 10 m, 15 m, 20 m and even up to > 30 m. Keeping in line with the demands of the game, often most sprints that occur during a completive match do not exceed 10 m in distance (18), therefore, a practitioner may want to that this into account when selecting the correct linear distance to keep it specific as possible.

Strength and power tests that are often used, not limited to, one or more of the following:

- Countermovement Jump (CMJ) with and without arm use

- 1RM test

- 3RM

- 5RM

- Squat Jump

Read more about the 4 Essential Tips for Administering Fitness Testing. For practitioners not working with gold-standard equipment or in non-elite environments, check out Fitness Testing on a Budget.

Program Design Ideas for Women Footballers

Periodisation looks to segment an overall program into specific periods. The largest one, a macro-cycle, is often the entire year or a period of multiple months or years that frequently reflects all training and matches. Within the macro-cycle, a mesocycle resides, which could last several weeks or months. Finally, within the mesocycle, there may be one or more micro-cycles that could be a week long but could last up to four weeks (9).

Working in women’s football, the best place to start is by looking at the overview of the entire season. Firstly, mapping out all known league matches, cup matches and any additional competitive fixtures that may occur. Around this, add in any contact time for technical and tactical sessions that the coaching staff wish to have. Once the macro-cycle is completed, the next step is to delve into a mesocycle block which may have coaching points, sessions or outcomes attached to them.

The micro-cycles can be pre-planned in advance, but are often subject to change, based on previous results and match outcomes. Fixture congestion and fixture changes are quite possible, so being adaptable is the key. In the event a game goes into added time which was not previously accounted for, the MDT may look to utilize a longer active recovery session the following day, or possibly, give players the full day off.

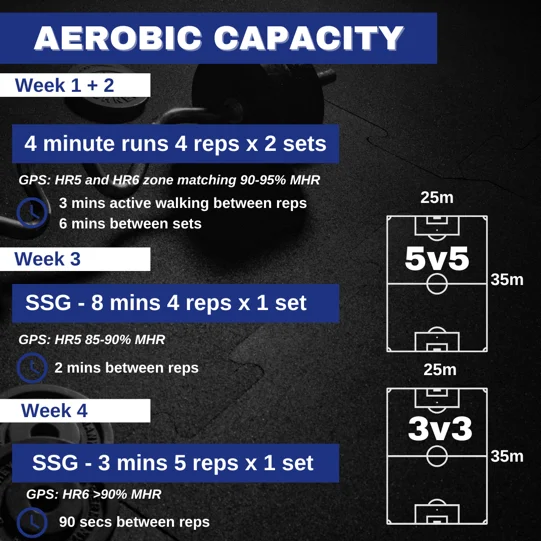

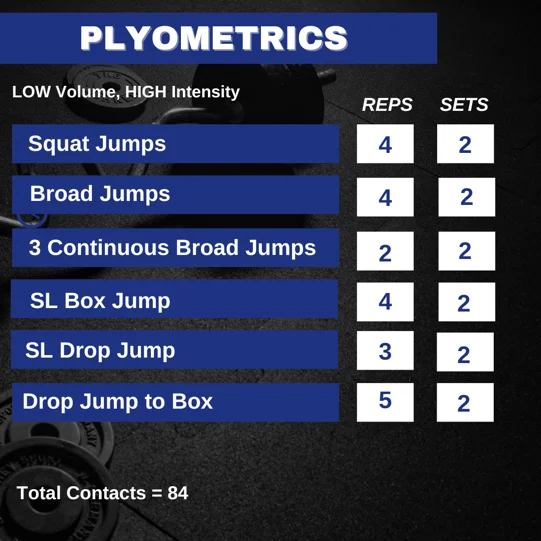

Speed, plyometrics and strength training can regularly be added into the main technical session as part of a warm-up or S&C segment. Specific sessions with a sole focus on speed mechanics may be beneficial, but for non-elite teams, it can be incorporated in creative ways during the regular training sessions scheduled.

Conclusion

The demands of women’s football that are outlined within this article aim to draw on all research conducted to date. With women’s football being banned for 50 years, the growth since 1971 has been on a constant rise, albeit, with the demands of the game changing to suit the times. Completing a Needs Analysis is essential to understand the demands a player faces in a game and therefore, create training strategies to help bridge the gap. As different movements occur, football draws on both the aerobic and anaerobic energy systems. Often, a practitioner may look to investigate aerobic capacity, strength and power, agility and change of direction, and high-speed or high-intensity running.

On the larger scale, normative data concludes that a female footballer should have a VO₂ max score between 49.4 – 57.6 ml⋅kg⋅min-1. Other research states that changes of direction occur every 4-6 seconds during a game. Sprint distances look to vary based on position but are often recorded as > 10 m in distance. These demands allow training strategies to be implemented based on the findings that current research has to offer. Practitioners must take into account considerations of the tactics and playing style, the effects the menstrual cycle could impose, potential and common injury threats, and the gap between elite and non-elite levels.

- The FA. ‘The Story of Women’s Football in England’. [ONLINE] Available at: [LINK]. [Accessed on 03 August 2023].

- FIFA. (2023) ‘FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023 Breaks New Records’. [ONLINE] Available at: [LINK]. [Accessed 08 August 2023].

- Gastin, P.B. (2012) ‘Energy Systems Interaction and Relative Contribution During Maximal Exercise’, Sports Medicine, (31), pp.725-742.

- Webster, D. (2012) ‘Energy Systems: How they work and when they are in use’, The Athletic Lab. [Accessed: 03 August 2023].

- Krustrup, P., Mohr, M., Ellingsgaard, H., Bangsbo, J. (2005). ‘Physical Demands during an Elite Female Soccer Game: Importance of Training Status’, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., 37(7), pp. 1242-1248.

- McArdle, W.D., F.I. Katch, and V.I. Katch. ‘Exercise Physiology’, 6th ed. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins. 2007.

- Iaia, F.M., Rampinini, E., Bangsbo, J. (2009) ‘High-Intensity Training in Football’, Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 4(3), pp.291-306.

- Datson, N., Hulton, A., Andersson, H., Lewis, T., Weston, M., Drust, B., Gregson, W. (2014) ‘Applied Physiology of Female Soccer: An Update’, Sports Med, 44(9)., pp. 1225-40.

- Baechle, T.R., Earle, R. W. ‘Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning’, 3rd ed. United States: National Strength and Conditioning Association. 2008.

- Turner, E., Munro, A., Comfort, P. (2013) ‘Female Soccer’, Strength and Conditioning Journal, 35(1), pp.51-57.

- Owen, A. ‘Football Conditioning – A Modern Scientific Approach’, SoccerTutor.com, 2016.

- Andersson, H. Å., Randers, M. B., Heiner-Møller, A., Krustrup, P., Mohr, M. (2010) ‘Elite Female Soccer Players Perform More High-Intensity Running When Playing in International Games Compared to Domestic League Games’, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 24(4), pp. 912-919.

- Martínez-Fortuny, N., Alonso-Calvete, A., Da Cuña-Carrera, I., Abalo-Núñez, R. (2023) ‘Menstrual Cycle and Sport Injuries: A Systematic Review’, Int. J. Res. Public Health, 20(4), pp. 3264.

- Ray, L., Muchalowski, M. (2018) ‘What is the Menstrual Cycle’, Clue.

- López-Valenciano, A., Raya-Gonźalez, J., Garcia-Gómez, J.A., Aparicio-Sarmientro, A., Sainz de Baranda, P., De Ste Croix, M., Ayala, F. (2021). ‘Injury Profile in Women’s Football: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, Sports Medicine, 51, pp.423-442.

- Boden, B.P., Dean, S., Feagin, J.A., Garrett Jr, W.E. (2000) ‘Mechanisms of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury’, Orthopedics, 23(6), pp.573-578.

- Arendt, E.A., Agel, J., Dick, R. (1999) ‘Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Patterns Among Collegiate Men and Women’, J Athl Train, 34(2), pp.86-92.

- Paterno, M.V., Rauh, M.J., Schmitt, L.C., Ford, K.R., Hewett, T.E. (2012) ‘Incidence of Contralateral and Ipsilateral Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) Injury After Primary ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport’, Clin J Sport Med, 22(2), pp.116-121.

- Griffin, J., Larsen, B., Horan, S., Keogh, J., Dodd, K., Andreatta, M., Minahan, C. (2020) ‘Women’s Football: An Examination of Factors That Influence Movement Patterns’, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(8), pp.2384-2393.