Early specialisation in youth athletes: Pros, cons and considerations

Early specialisation is one of the hottest debates in youth development circles. But what is all the fuss about, and which path is preferable?

Early Specialisation in youth athletes: What’s all the fuss about?

So, you want to be a professional athlete? Who doesn’t!

In society, you are taught that if you want to get better at something, you must repeat the process until mastery is achieved. School, employment, even relationships require deliberate practice to develop and maintain them. However, this can also backfire.

Take a talented mathematician in school as an example – should they just focus on math at the expense of science and English? No. Parents, teachers and students would understand that their holistic education is really important.

So why do we do the opposite when it comes to sport? Sit back, pause that podcast, and enjoy.

Specialisation case study

This is Tim.

Tim wants to be a professional football player. His parents take him to every training session, buy him all the new gear and pay for the top coaches to develop his football skills in hopes that it will improve his chances of success.

When Tim’s parents take him out, they are always boasting to their friends about how he is going to be a professional football player. By the ripe age of 10, Tim is never seen out of a football kit. He pretends his bike is a Range Rover and even rocks the Jack Grealish hair band at school – as you can see, he looks good.

Tim’s best friend, Rob, also plays football but is encouraged by his teachers and parents to play rugby and cricket as well. He also dabbles in a bit of casual swimming on the weekends with his other friends. Rob’s support network knows that intensive training, coupled with inadequate strength and conditioning provision and nutrition, is a recipe for disaster (see what I did there?). In addition, they know that focusing on one sport may negate the many benefits associated with multi-sport participation.

Fast forward six years, Tim and Rob are both playing on the same team at the same level, and their coaches are thinking about who is going to progress through the system.

Tim is really good, but keeps picking up small injuries throughout the season and has a limited repertoire of skills.

Rob, on the other hand, is robust and is socially more rounded from participating in other sports (e.g., rugby). Rob is an example of a late-specialisation athlete who has focused on a sport a bit later on, allowing him to refine and hone his technique through a variety of activities.

Rob has been filling his toolbox with a variety of tools (i.e., movements and skill sets), whereas Tim has simply sharpened the one tool he has. Tim has fallen victim to the early specialisation conundrum, which impacts so many youths in various systems.

Some of the negative consequences of specialising too early in one sport have been briefly demonstrated above. Put simply, Tim has made football his identity.

Let’s go down a path where Tim isn’t selected for an elite team. To Tim, this may feel like a criticism of everything he stands for, and although that’s not the case, as a young athlete, it can certainly be hard to deal with. None of us enjoy the feeling of rejection.

Tim is also going through adolescence, where he will experience significant alterations in hormonal status, physical growth, and social and cognitive processes. Now he’s not just lost his identity (“I know Tim, that’s the guy who wants to be the footballer”), but is also going through one of the biggest physical, emotional, and cognitive transitions of his life (adolescence). What a tough time.

Remember those pesky little injuries Tim kept getting? Well, youth athletes who specialise early are more prone to growth-related injuries (e.g., Osgood Schlatter’s disease), fractures, rotator cuff injuries, and ACL injuries – which are more prevalent in females. These can all be classified as overuse injuries, which are mostly due to repeated physical stress from performing similar movement patterns over and over again. In addition to these injuries, Tim has missed some parts of his childhood, which has contributed to him feeling somewhat out of touch with his peers.

Tim, like many, faces a conundrum created by society’s desires for immediate gratification, opportunities for social recognition and scholarships, and most frequently, adults imposing their own dreams and wishes on their child.

Is this always the case?

Okay, so I’ve sent you down one pathway (which admittedly was a little grim), now let’s go down another. Some sports, such as gymnastics, tennis, or ballet must be pursued from a young age, as these athletes can compete professionally from as young as 15. In addition, the skill sets required to be successful are often refined and honed over time to develop high levels of proficiency.

Take a look at this video of Simone Biles competing for the USA in gymnastics. Could you start this at 16? Of course. But in order to develop the strength, mobility, flexibility and skill required to do so, it would take years of expert coaching. Furthermore, by 16 years of age, you’ve likely already developed a whole host of bad movement habits (e.g., limited thoracic extension from excessive sitting), which make a back handspring look like something that should be in a Marvel movie, not the gym.

Specialising early in a sport can certainly have some advantages. For instance, participating within one environment (e.g., rugby) makes an individual very familiar with the language, culture, and tactics adopted within a club or sport. In return, coaches may perceive these individuals to be more receptive to the “way things are done” and treat them as a safe investment.

Early specialisation can and does work, but allowing athletes to sample other movements, for example, placing a tennis player into a game of football, would not harm the development of their primary sport skills – their tennis serve in this case. Instead, it can aid the development of other relevant performance characteristics – such as their footwork and ability to speed up (accelerate) and slow down (decelerate).

What can you do?

Early specialisation can increase the likelihood of burnout and overtraining, so it’s important players engage in a variety of sports to avoid tedium. Here are my top four tips to avoid some of the issues associated with early specialisation:

Engage in activities that transfer to other sports

Think of a gymnast who at 15, decides that gymnastics is no longer for them. Which of their existing skills lend to other sports? They may have spent the last 10 years in static positions, with minimal focus on landing with their feet apart, evading, accelerating, throwing and catching – so, their skillset is clearly very specific to gymnastics. Therefore, it may be time to change it up and play some tennis, engage in a bit of parkour, or develop a new skill (e.g., rugby pass) in your free time. This will help keep you well-rounded whilst combatting some of the overuse risks discussed above.

Find a coach who encourages you to participate in a wide range of sports

Coaches shouldn’t make you feel bad or feel as though it will impact your selection in the future. If they do, it could be time to find a new one. In addition, playing sports should be fun, so it’s more than okay to want to play for your school team as well as your chosen club. If your coach understands what’s best for you, they may even excuse you from training if you’ve had a busy sports schedule – they should respect your need to rest and recover.

Consider the environment you create as an individual for your peers

Do you actively create an environment that celebrates and encourages sport diversity? When a teammate does really well in another sport, celebrate it with them, their parents, the club, and the coach. This will foster a culture where everyone feels like they can, and should, play other sports to develop their skill set.

Develop confidence in being a kid

Jump a stream, climb a tree and learn to fall. These are invaluable athletic skills that we must develop outside of sport. Your internal fear gauge (e.g., concluding “I simply cannot jump that height”) is a pretty good indicator of how safe a task is. This advice is not just for the ‘young’ however – you are never too old to go out and discover what your body can do!

Am I specialising?

It all comes down to this question. Even after reading this, you may feel like early specialisation is really bad – it isn’t. But, taking small steps that allow younger athletes to sample different movement patterns, personalities, and skills can be the difference between reaching success and struggling to unlock their potential.

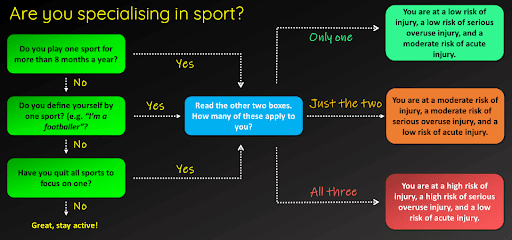

This small graphic below, adapted from Myer et al. (2015), is a fantastic guide for players, parents and coaches to determine whether they, their child or their athlete, are in the realm of early specialisation.

Figure 1: (Adapted from Myers et al., (2015), p2).

If by the end of this process you are in the green box on the right, you might like to think about engaging in a basic level strength and conditioning program – focusing on movements such as the squat, hinge, and lunge patterns, push and pull variations, and bracing (e.g., planks). This will reduce your likelihood of serious injury and prevent those annoying little niggles from occurring (e.g., rolling your ankle).

If you arrive in the orange box, you should consider the above advice too, but more specifically, focus on some key injury prevention exercises such as Nordic hamstring curls, thoracic mobility, hip strength, and trunk control. You are approaching the status of early specialised athlete and need to monitor your schedule. Any additional stress (i.e., exams, increased fixture demands, or poor sleep) will elevate your risk of injury.

Find yourself in the red box? Time to seriously reconsider your weekly schedule. You are an early specialised athlete. If you answered yes to all three questions on the left, you could be at a high risk of injury, both general and overuse, which could mean missing a lot of time from your sport. Consider engaging in other sports and think about seeking the help of a strength and conditioning coach who focuses solely on youth.

Final comments

In simple terms, early specialisation may be defined as practice with high levels of domain specificity, focusing on one sport only. Late specialisation occurs when an individual enters the sport “late” – after sampling a variety of sports skills beforehand. Both have benefits but are largely context-dependent (e.g., based on the requirements of the sport).

In most cases, intense training in one sport at the exclusion of others should be delayed until middle to late adolescence, as early diversification is more likely to lead to success. For example, when the backgrounds of 300+ female intercollegiate athletes were investigated, it was discovered the majority had their first organised experiences in other sports. On the contrary, only 17 percent had exclusively participated in their current sport. This typifies the risk of early specialisation in youth, where the misconception that “more is better” doesn’t always ring true. However, it is important to acknowledge that early specialisation can work if the sport/education provider considers the risk of single-sport participation by ensuring that practice is diverse and many transferable sport skills are involved.

[optin-monster slug=”nhpxak0baeqvjdeila6a”]