Contents of Article

- The problem

- What’s the solution?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the author

The problem

If you’re in the business of improving an athlete’s performance, then knowing their maximal strength is very important. An athlete’s maximal strength is the total amount of force they can produce in a given movement (e.g. back squat) and is also commonly referred to as their ‘maximal force capacity’.

While it’s important to understand your athlete’s maximal force capacity, unless you have a bulbous budget to work with, simply measuring it can be a difficult task. For example, a force plate will set you back tens of thousands of dollars [1], a dynamic one-repetition maximum (1RM) test will take a long time to administer, cause fatigue and muscle soreness, and not even give accurate results if the athlete is being tested on a day when they’re fatigued.

You could also try to estimate an athlete’s 1RM using a velocity-based training (VBT) device; however, as the research has shown, this method isn’t very accurate [2]. The only way to get more reliable 1RM estimates using VBT devices is to use loads very close to an athlete’s 1RM [3], but that then defeats the purpose of estimating it in the first place.

What’s the solution?

As technology advances, most things tend to get easier, quicker, and cheaper, and there seems to be no exception in the world of sports performance.

With advances in technology and the success of recent research [4], any coach on a shoestring budget can now accurately measure an athlete’s maximum strength quickly and easily using a device known as a ‘crane scale’. A crane scale (Figure 1) is what is known as a ‘load cell’ or ‘dynamometer’ and it’s simply used to measure the weight of something. It typically costs less than $100 (USD). These devices are also almost small enough to fit inside your pocket, making them perfect from a portability standpoint.

Because of the cheap cost and portability of the device, a recent study which was reviewed in issue #25 (November 2018) of our Performance Digest was conducted by Urquhart and colleagues [4] to test whether it could be used to accurately measure an athlete’s 1RM in an isometric movement (i.e. the isometric mid-thigh pull). If you wish to read the full details of the study and our expert review of it, including practical takeaways and expert comments, then click here for all the details.

What the researchers found

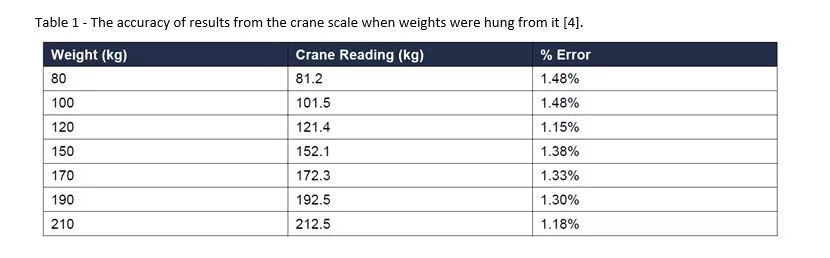

The crane scale was shown to have a near-perfect relationship with the force plate. Based on the data collected and the statistical breakdown, it appears a commercial hand scale, particularly the Crane model used, was reliable enough to be used as a crude indicator of isometric strength.

The authors also measured the accuracy of the crane scale against the force plate when measuring an athlete’s isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP)* and found that the average difference between the two was only 2.7 % – a very small difference indeed.

*If you want to know more about what the IMTP is and why it’s the preferred exercise for measuring maximal strength (i.e. maximal force capacity), then we highly recommend you read this article on the topic.

Conclusion

Based on this information and the excellent work of Urquhart and colleagues, coaches/practitioners around the world who are working on a shoestring budget can simply measure their athlete’s maximal strength in a quick and easy fashion and feel confident that the results they’ve got are accurate.

This is tremendously helpful for thousands of coaches out there who are constantly “pushing the envelope” and finding new and exciting ways to provide the best service possible to their athletes. If you’re one of these coaches/practitioners who are constantly trying to evolve your practice but don’t have a big budget to work with, then the crane scale is going to be a fantastic tool to add to your toolbox.

Not only that, but the crane scale can be used for many different purposes, the most popular of which are:

- Measure an athlete’s maximum strength.

- Measure the effectiveness of training interventions.

- Reduce injury risk.

- Monitoring fatigue (understand the athlete’s “freshness/readiness to train”).

- Comparing athletes and creating competition.

- Measuring between-limb asymmetries.

- 2019. Force Plates – Do you need one? [ONLINE] Available at: https://kinetic.com.au/pdf/Force_Plates.pdf. [Accessed 15 April 2019]. https://kinetic.com.au/pdf/Force_Plates.pdf

- Banyard, HG, Nosaka, K, and Haff, GG. Reliability and validity of the load–velocity relationship to predict the 1RM back squat. J Strength Cond Res 31(7): 1897–1904, 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27669192

- Jidovtseff, B., Harris, N.K.., Crielaard, J.M., Cronin, J.B. Using the load-velocity relationship for 1RM prediction. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 25: 267-270. 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19966589

- Michael N. Urquhart, Chris Bishop & Anthony N. Turner. (2018) Validation of a crane scale for the assessment of portable isometric mid-thigh pulls. Journal of Australian Strength & Conditioning. 26(5):28-33. http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23039/