Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is the Stretch-Shortening Cycle (SSC)?

- What are the mechanisms of the Stretch-Shortening Cycle?

- Electromechanical Delay (EMD)

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

- Comments

Summary

The stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) refers to the ‘pre-stretch’ or ‘countermovement’ action that is commonly observed during typical human movements such as jumping. This pre-stretch allows the athlete to produce more force and move quicker. Though there is controversy surrounding the mechanics responsible for the performance improvements observed from using the SSC, it is likely to be a combination of the active state and the storage of elastic energy within the tendon. Due to the negative effects of the electromechanical delay, it may be suggested that training methods which improve muscular pre-activity, such as plyometric and ballistic training, may be beneficial for improving athletic performance.

What is the Stretch-Shortening Cycle (SSC)?

Athletes have been shown to jump 2-4 cm higher during the countermovement jump (CMJ) than they can during the squat jump (SJ) (1). This is simply because the CMJ incorporates a pre-stretch dropping action when compared to an SJ, which initiates the movement from a static position without the use of a pre-stretch (2). This pre-stretch, or ‘countermovement’ action is known as the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) and is comprised of three phases (eccentric, amortization, and concentric) (Figure 1) (3). Images A-B display the eccentric phase, image C demonstrates the amortisation phase, and images D-E represent the concentric phase of the SSC.

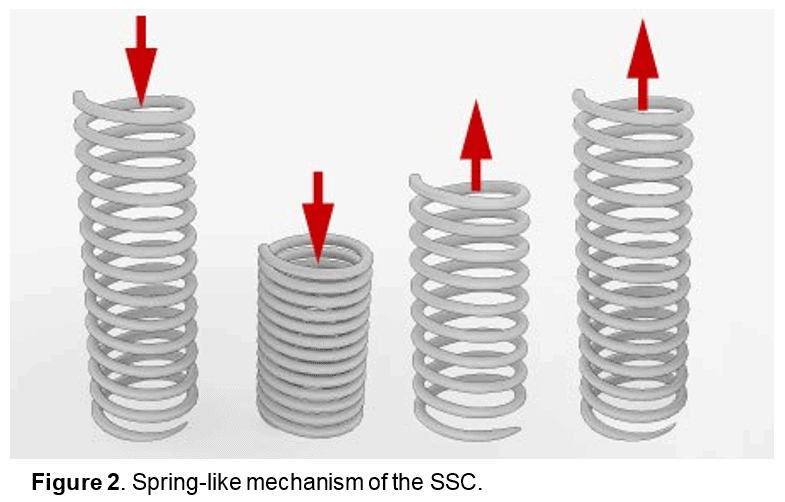

The SSC is described as a rapid cyclical muscle action whereby the muscle undergoes an eccentric contraction, followed by a transitional period prior to the concentric contraction (4). This muscle action is also sometimes referred to as the reverse action of muscles (5). The action of the SSC is perhaps best described as a spring-like mechanism, whereby compressing the coil causes it to rebound and therefore jump off a surface or in a different direction (Figure 2). Increasing the speed at which the coil is compressed or how hard it is pressed down (amount of force applied) will result in the spring jumping higher or farther. This is known as the ‘rate of loading’, and increasing this will often mean the spring will jump higher or farther. Therefore, a jump that incorporates a ‘run-up’ will often allow an athlete to jump higher or farther than a jump from a static position because of an increase in the rate of loading (6, 7, 8).

The SSC does not only occur during single-bout jumping or rebounding movements but also during any form of human movement when a limb changes direction. For example, during walking, jumping, running, twisting or even lowering and then raising your arm. As the limbs are continuously changing direction, there is constant use of the SSC in order to change the direction the limb is moving. As some movements are much faster than others (e.g. sprinting vs. walking), there are great differences in the speed of the SSC. Consequently, the SSC has been separated into two categories based on the duration of the SSC:

- Fast-SSC: <250 milliseconds (ms)

- Slow-SSC: >250 ms

Table 1 provides some examples of common exercises and their potential SSC classification. As displayed in Table 1, a long jump is typically classified as a fast-SSC movement as it has a ground contact time of 140-170 ms (9). Whereas race walking, which has a ground contact time of 270-300 ms is commonly classified as a slow-SSC movement (10).

| Exercise | Ground contact time | SSC Classification |

| Race walking (10) | 270-300 | Slow |

| Sprinting (11) | 80-90 | Fast |

| Countermovement jump (CMJ) (12) | 500 | Slow |

| Depth Jump (20-60cm) (2,3) | 130-300 | Fast / Slow |

| Long Jump (13) | 140-170 | Fast |

| Multiple Hurdle Jumps (5) | 150 | Fast |

As measuring the duration of the SSC at each contributing joint (e.g. ankle, knee, hip) during a jumping exercise is problematic, researchers have often questioned the ability to measure the SSC indirectly by analysing the ground contact times. As a result, researchers have looked for relationships between ground contact times and coupling time*. Strong relationships have been found between coupling time and exercises with ground contact times ranging from 270-2500 ms (16, 17).

However, no relationships were observed in exercises with ground contact times of 400-800 ms (17). This, therefore, questions the reliability of classifying exercises with ground contact times of < 850 ms into particular SSC categories based on their ground contact duration. For example, simply classifying race walking as a slow-SSC movement because it has a ground contact time between 270-300 ms. Though this is often common practice, understanding the issue with doing so is important.

*Coupling time is the amortisation/isometric phase of the SSC which connects the eccentric to the concentric phase – hence the term ‘coupling’, as it couples the two together. Or in other words, coupling time is defined as the transition between the eccentric and concentric phases of the SSC (16).

What are the mechanisms of the Stretch-Shortening Cycle?

There are numerous neurophysiological mechanisms thought to contribute to the SSC, some of which include: storage of elastic energy (18, 19, 20, 21), involuntary nervous processes (22, 23), active state (1, 24), length-tension characteristics (25, 26), pre-activity tension (27, 28) and enhanced motor coordination (1, 24). Despite this large list, it is commonly agreed there are three primary mechanics responsible for the performance-enhancing effects of the SSC (2).

These three mechanisms are:

- Storage of Elastic Energy

- Neurophysiological Model

- Active State

Storage of Elastic Energy

The concept of elastic energy is similar to that of a stretched rubber band. When the band is stretched, there is a build-up of stored energy, which when released, causes the band to rapidly contract back to its original shape. The amount of stored elastic energy (sometimes referred to as ‘strain’ or ‘potential’ energy) is potentially equal to the applied force and induced deformation (5). In other words, the amount of force used to stretch the band should be equivalent to the amount of force produced by the band in order to return to its pre-stretched state.

In humans, this stretch and storage of elastic energy is instead placed upon the muscles and tendons during movement. However, due to the elastic properties of the tendon, it is commonly agreed that the tendon is the primary site for the storage of elastic energy (29, 30). Unlike muscles, the tendons cannot be voluntarily contracted, and as a result, they can only remain in their state of tension.

This means the muscle must contract and stiffen prior to the beginning of the SSC during ground contact – known as ‘muscular pre-activity’. The muscle must then remain contracted/ stiff during the first two processes of the SSC (eccentric and amortisation phases) in order to transmit the isometric forces into the tendon. This causes the deformation/ lengthening of the tendon and the development of the storage of elastic energy.

During the concentric phase of the SSC (often referred to as the ‘positive acceleration’ phase), the muscle is then able to concentrically contract and provide additional propulsive force (2). Failing to stiffen during the eccentric and amortisation phases, means the performance-enhancing effect of the SSC will be lost and the joint would likely collapse. This demonstrates the importance of muscle stiffness during the SSC and its ability to improve performance. It also suggests that athletes with higher levels of muscular strength can absorb more force (i.e. higher rate of loading), and therefore have a better ability to use the SSC.

An abundance of research has demonstrated that stronger athletes have a better ability to store elastic energy than less-strong individuals (31, 32, 33). Elite athletes from both power- and endurance-based sports have also been demonstrated to possess a superior ability to store elastic energy (31, 32). Furthermore, efficient utilisation of the SSC during sprinting has been shown to recover approximately 60% of total mechanical energy, suggesting the other 40% is recovered by metabolic processes (34, 35). In aerobic long-distance running, higher SSC abilities have also been shown to enhance running economy – suggesting that athletes with a better SSC capacity can conserve more energy whilst running (33, 36, 37). This indicates the importance of the SSC for both energy release and energy conservation. However, this storage of the elastic energy within the tendon cannot last forever and has been shown to have a half-life of 850 milliseconds (38).

Neurophysiological Model

The muscles and tendons contain sensory receptors known as ‘proprioceptors’, these send information to the brain about changes in length, tension and joint angles (39). The proprioceptors within the muscle are known as ‘muscle spindles’, whilst those in the tendon are called ‘Golgi tendon organs’.

When a muscle is forcefully lengthened, the muscle spindles engage a stretch-reflex response to prevent over-lengthening and limit the possibility of injury. The engagement of these muscle spindles is thought to cause increased recruitment of motor units and/ or an increased rate coding effect (40, 41). An excitation of either or both of these neural responses would lead to a concurrent increase in concentric force output and may, therefore, explain the performance-enhancing effects of the SSC.

The increase in concentric force output would therefore then lead to an enhanced power output during sporting movements (e.g. jump), and thus may improve performance. However, many studies have reported no increase in muscle activation after a pre-stretch activity (e.g. CMJ) when compared to non-pre-stretch activity (e.g. SJ) (26, 42, 43). This suggests that muscle spindle reflex activity does not have any impact on the increased force by the SSC (1).

Furthermore, when a muscle is forcefully lengthened, the Golgi tendon organs (GTO) engage an opposite stretch-reflex response to the muscle spindles. Their role is to inhibit (i.e. prevent) the excitation of the muscle spindles during forceful over-lengthening to prevent the possibility of injury (5). Though this may seem like a bizarre trade-off between the muscle spindles and the GTO, the muscle spindles activate when the muscle-tendon unit is forcefully lengthened, whilst the GTO activate when the forceful lengthening becomes too large (39).

Due to the inhibitory stretch-reflex response of the GTO, it is thought this may counteract the contraction action of the muscle spindles. If so, this would mean that the GTO inhibits the high-muscular stiffness needed during the SSC and therefore reduces the concentric force output and subsequent performance (2). In fact, research has shown that muscle activation levels – and therefore muscle stiffness – have been reduced during the early phases of the SSC in individuals who are unaccustomed to intense SSC movements (28).

Interestingly, however, 4-months of plyometric training has been shown to reduce this GTO inhibitory effect (disinhibition) and increase muscular pre-activity and muscle-tendon stiffness (27). As a result, it appears that effective training methods (e.g. plyometrics) can reduce or even eliminate the potential negative effects observed from the GTO inhibitory effect.

Active State

The active state is the period of time in which force can be developed during the eccentric and amortisation phases of the SSC before any concentric contraction occurs. For example, during the ‘countermovement’ or ‘dropping’ action of the CMJ, the active state is developed during the eccentric and amortisation phases. The unpinning belief is that exercises that possess longer eccentric and amortisation phases of the SSC will allow more time for the formation of cross-bridges, therefore enhancing joint moments, and thus improving concentric force output. Increasing the amount of force, and the time available for force to be developed typically leads to a concurrent increase in the impulse (Impulse = Force x Time) (24, 44). In other words, increasing the force application will lead to improvements in power output and therefore athletic performance.

There is widespread agreement to suggest the active state is the largest contributor to the performance-enhancing effects of the SSC, as it allows for a greater build-up of force prior to concentric shortening (1, 24, 44, 2).

What is the Electromechanical Delay (EMD)?

The electromechanical delay (EMD) refers to a neural and physiological delay in the production of mechanical force. This simply implies the muscles cannot generate and transmit force to the skeletal system instantaneously, instead, there is a slight delay. A delay in the production of mechanical force can, therefore, lead to a reduction in performance (24).

Currently, there are numerous components that have been suggested to contribute to this delay:

- Finite rate of increase in muscle stimulation by the central nervous system.

- Propagation of the action potential on the muscle membrane.

- Time constraints of calcium release and cross-bridge formation.

- Interaction between the contractile filaments and the series of elastic components.

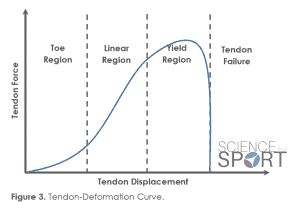

- Toe region of the tendon.

As a complete analysis of all these neurophysiological factors is beyond the scope of this article and readily available in exercise physiology textbooks, only the toe region will be explained.

The toe region of the SSC, otherwise simply explained as ‘slack within the tendon’ is present at the very beginning of the SSC. To simplify this concept, imagine a coiled-up piece of string that is being pulled from both ends in order to straighten it out and create tension. Well this ‘slack’, before the string is straight, is referred to as the ‘toe-region’. It is recognised that this slack within the tendon delays the time in which muscle-tendon stiffness and concentric force can be generated – simply the time taken to straighten the string and create tension (45) (Figure 3). Therefore, the toe region reduces the time available to generate force during the SSC and thus reduces concentric force output.

Due to the negative effects of the EMD on mechanical force, it has been proposed that optimising muscular pre-activity may reduce or even counteract the effects of EMD by exciting the muscle and creating muscle-tendon stiffness prior to the start of the SSC (2). As a result, training methods which improve pre-activity, such as plyometric and ballistic training, may be beneficial for the optimization of the SSC (27).

Conclusion

The SSC, otherwise known as the reverse action of muscles, is a spring-like mechanism shown to enhance athletic performance both in explosive- and endurance-based sports. Well-trained athletes appear to possess better SSC capacities than less- or non-trained individuals and thus highlight the necessity to optimise this property to enhance athleticism. Despite the long list of mechanisms proposed to influence the effects of the SSC, the active state is commonly believed to be the primary contributor. The time to develop mechanical force is negatively affected by the electromechanical delay, and thus attempts to maximise muscular pre-activity via particular training methods (e.g. plyometrics) should be profound.

- Bobbert MF and Casius LJ. Is the countermovement on jump height due to active state development? Med Sci Sport Exerc 37: 440–446, 2005. [PubMed]

- Turner, A.N. & Jeffreys, I. (2010). The stretch-shortening cycle: proposed mechanisms and methods for enhancement. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 17, 60-67. [Link]

- Komi PV (1984) Physiological and biomechanical correlates of muscle function: effects of muscle structure and stretch-shortening cycle on force and speed. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 12:81-121 [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.S., Oliver, J.L., Hughes, M.G., and Williams, C.A. (2012). The effects of 4-weeks of plyometric training on reactive strength index and leg stiffness in male youths. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(10), pp.2812–2819. [PubMed]

- Zatsiorsky VM and Kraemer WJ. Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2006. pp. 33–39. [Link]

- Aura O and Viitasalo JT. Biomechanical characteristics of jumping. Int J Sports Biomech 5: 89–97, 1989. [Link]

- McBride JM,McCaulleyGO, and Cormie P. Influence of preactivity and eccentric muscle activity on concentric performance during vertical jumping. J Strength Cond Res 23: 750–757, 2008. [PubMed]

- McCaulley GO, Cormie P, Cavill MJ, Nuzzo JL, Urbiztondo ZG, and McBride JM. Mechanical efficiency during repetitive vertical jumping. Eur J Appl Physiol 101: 115–123, 2007. [PubMed]

- Stefanyshyn, D. & Nigg, B. (1998) Contribution of the lower extremity joints to mechanical energy in running vertical jumps and running long jumps. Journal of Sport Sciences, 16, 177-186. [PubMed]

- Padulo, J, Annino, G, D’Ottavio, S, Vernillo, G, Smith, L, Migliaccio, GM, and Tihanyi, J. Footstep analysis at different slopes and speeds in elite race walking. J Strength Cond Res 27(1): 125–129, 2013 [PubMed]

- Taylor, M. J. D., & Beneke, R. (2012). Spring Mass Characteristics of the Fastest Men on Earth.International journal of sports medicine, 33(8), 667.[PubMed]

- Laffaye, G., & Wagner, P. (2013). Eccentric rate of force development determines jumping performance. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering, 16(1), pp.82–83. [Link]

- Ball, NB, Stock, CG, and Scurr, JC. Bilateral contact ground reaction forces and contact times during plyometric drop jumping. J Strength Cond Res 24(10): 2762–2769, 2010. [PubMed]

- Walsh, M, Arampatzis, A, Schade, F, and Bruggemann, G. The effect of drop jump starting height and contact time on power, work performed and moment of force. J Strength Cond Res 18: 561–566, 2004. [PubMed]

- Flanagan EP and Comyns TM. The use of contact time and the reactive strength index to optimise fast stretch-shortening cycle training. Strength Cond J 30: 33– 38, 2008. [Link]

- Kobsar, D., & Barden, J. (2011). Contact time predicts coupling time in slow stretch-shortening cycle jumps. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 25(1), pp.51-52. [Link]

- Zameziati, K., Morin, J.B., Deiuri, E., Telonio, A., & Belli, A. (2006). Influence of the contact time on coupling time and a simple method to measure coupling time. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 96, pp.752–756. [PubMed]

- 18. Potteiger JA, Lockwood RH, Haub MD, Dolezal BA, Almuzaini KS, Schroeder JM, and Zebas CJ. Muscle power and fiber characteristics following 8 weeks of plyometric training. J Strength Cond Res 13: 275–279, 1999. [Link]

- Spurrs RW, Murphy AJ, and Watsford ML. The effect of plyometric training on distance running performance. Eur J Appl Physiol 89: 1–7, 2003. [PubMed]

- McBride JM,McCaulleyGO, and Cormie P. influence of preactivity and eccentric muscle activity on concentric performance during vertical jumping. J Strength Cond Res 23: 750–757, 2008. [PubMed]

- Myer GD, Ford KR, Brent JL, and Hewett TE. The effects of plyometric vs. dynamic stabilization and balance training on power, balance, and landing force in female athletes. J Strength Cond Res 20: 345–353, 2006. [PubMed]

- Bosco C, Komi PV, and Ito A. Pre-stretch potentiation of human skeletal muscle during ballistic movement. Acta Physiol Scand 111: 135–140, 1981. [PubMed]

- Bosco C, Montanari G, Ribacchi R, Giovenali P, Latteri F, Iachelli G, Faina M, Coli R, DalMonte A, Las RosaM, CortelliG, and Saibene F. Relationship between the efficiency of muscular work during jumping and the energetic of running. Eur J Appl Physiol 56: 138–143, 1987. [PubMed]

- Bobbert MF, Gerritsen KGM, Litjens MCA, and Van Soest AJ. Why is countermovement jump height greater than squat jump height? Med Sci Sports Exerc 28: 1402–1412, 1996. [PubMed]

- Ettema GJ, Huijing PA, and De Hann A. The potentiating effect of pre-stretch on contractile performance of rat gastrocnemius medialis muscle during subsequent shortening and isometric contractions. J Exp Biology 165: 121– 136, 1992. [PubMed]

- Finni T, Ikegawa S, Lepola V, and Komi P. In vivo behaviour of vastus lateralis muscle during dynamic performances. Eur J Sport Sci 1: 1–13, 2001. [Link]

- Kyrolainen H, Komi PV, and Kim DH. Effects of power training on neuromuscular performance and mechanical efficiency. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1: 78–87, 1991. [Link]

- Schmidtbleicher D, Gollhofer A, and Frick U. Effects of stretch shortening time training on the performance capability and innervation characteristics of leg extensor muscles. In: Biomechanics XI-A (Vol 7-A). DeGroot G, Hollander A, Huijing P, and Van Ingen Schenau G, eds. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Free University Press, 1988. pp. 185–189. [Link]

- Kubo K, Kawakami Y, and Fukunaga T. Influence of elastic properties of tendon structures on jump performance in humans. J Appl Physiol 87: 2090–2096, 1999. [PubMed]

- Lichtwark GA, and Wilson AM. Is Achilles tendon compliance optimised for maximum muscle efficiency during locomotion? J Biomech 40: 1768–1775, 2007. [PubMed]

- Hobara H, Kimura K, Omuro K, Gomi K. Muraoka T, Iso S, and Kanosue K. Determinants of difference in leg stiffness between endurance- and power-trained athletes. J Biomech 41: 506–514, 2008. [PubMed]

- Arampatzis A, Karamanidis K, Morey- Klapsing G, De Monte G, and Stafilidis S. Mechanical properties of the triceps surae tendon and aponeurosis in relation to intensity of sport activity. J Biomech 40: 1946–1952, 2007. [PubMed]

- Dalleau G, Belli A, Bourdin M, and Lacour JR. The spring-mass model and the energy cost of treadmill running. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 77: 257–263, 1998. [PubMed]

- Voigt M, Bojsen-Moller F, Simonsen EB, and Dyhre-Poulsen P. The influence of tendon Youngs modulus, dimensions and instantaneous moment arms on the efficiency of human movement. J Biomech 28: 281–291, 1995. [PubMed]

- Verkhoshansky YV. Quickness and velocity in sports movements. N Stud Athletics. 11: 29–37, 1996. [Link]

- Heise GD and Martin PE. ‘‘Leg spring’’ characteristics and the aerobic demand of running. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30: 750– 754, 1998. [PubMed]

- Goldspink G. Muscle energetic and animal locomotion: In Mechanics and Energetic of Animal Locomotion. Alexander Mc and Goldspink G, eds. London, United Kingdom: Chapman and Hill, 1977. pp. 57–81. [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.J., Murphy, A.J., and Pryor, J.F. (1994). Musculotendinous stiffness: Its relationship to eccentric, isometric, and concentric performance. Journal of Applied Physiology, 76(1), pp.2714–2719. [PubMed]

- McArdle, W.D., Katch, F.I., Katch, L.K., (2010). Exercise physiology: Nutrition, energy, and human performance, 7th London: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Link]

- Butler, R.J., Crowell, H.P., and Davis, I.M. (2003). Lower extremity stiffness: Implications for performance and injury. Clinical Biomechanics, 18(1), pp.511–517. [PubMed]

- Bosco, C., Komi, P.V., and Ito, A. (1981). Pre-stretch potentiation of human skeletal muscle during ballistic movement. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 111(17), pp.135–140. [PubMed]

- Kubo K, Morimoto M, Komuro T, Yata H, Tsunoda N, Kanehisa H, and Fukunga T. Effects of plyometric and weight training on muscle-tendon complex and jump performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 1801–1810, 2007. [PubMed]

- Thompson DD and Chapman AE. The mechanical response of active human muscle during and after stretch. Eur J Appl Physiol 57: 691–697, 1998. [PubMed]

- Van Ingen Schenau GJ, Bobbert MF, and De Hann A. Mechanics and energetics of the stretch shortening cycle: A stimulating discussion. J Appl Biomech 13: 484– 496, 1997. [Link]

- Hill, A.V. (1938). The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. Proceedings of the Royal Social B, 126, pp.136–195. [Link]