Contents of Article

- Summary

- What is a tactical athlete?

- What is tactical strength and conditioning?

- A theoretical model for tactical periodisation

- Why is tactical strength and conditioning important?

- What is the future of tactical strength and conditioning?

- What future research is needed with tactical strength and conditioning?

- Conclusion

- References

- About the Author

Summary

Tactical strength and conditioning is the application of strength and conditioning principles in a tactical (e.g. military, law enforcement, etc.) training environment. The term “tactical athlete” can refer to police officers, Tier 1 soldiers, firefighters, or even emergency medical service personnel.

Despite promising growth over the past few years within various tactical organisations, there is still a fair amount of confusion as to what exactly tactical strength and conditioning should look like. Highlighting unique challenges, identifying common solutions, and exploring current and future research will make it easier to optimise the performance of tactical athletes at all levels.

What is a tactical athlete?

The importance of the tactical athlete and the role they play in the battlespace has been appreciated for centuries. As far back as 1866, Dr. Jonathan Letterman is quoted as stating “the leading idea is to strengthen the hands of the Commanding General by keeping his army in the most vigorous health, thus rendering it, in the highest degree, efficient for enduring fatigue and privation, and for fighting” (15).

However, despite the common belief that a healthier soldier is a better soldier, it was not until recently that the term “Human Performance Optimisation” emerged and the need for utilising cutting-edge strength and conditioning principles with warfighters became apparent (1).

Performance programmes within militaries around the world have been funded to try and determine the best approach for maximising the investment in the tactical athlete’s health and longevity (1, 9, 10, 13). While the exact details of these projects are beyond the scope of this article, the general principles behind tactical strength and conditioning are worth discussing.

What is tactical strength and conditioning?

Before determining what tactical strength and conditioning is, it is important to discuss what it is not. Oftentimes within early-stage tactical performance programmes, there is a misguided attempt to directly apply the traditional sport model of strength and conditioning principles to the warfighter. Popular concepts such as linear periodisation, in-season versus off-season training, de-loading, etc. rarely find footing in the programmes that successfully prepare soldiers for today’s organic and fluid battlespace and deployment schedule. In fact, one could argue these concepts can create negative implications to the athletes’ training.

With that in mind, an altogether different definition needs to be considered. Tactical strength and conditioning can be thought of as a multidisciplinary approach to the repair, maintenance, and performance optimisation of the tactical athlete in order to maximise their effectiveness on the battlefield (7, 9, 10). Bear in mind the term “tactical athlete” could just as easily refer to police officers, Tier 1 soldiers, firefighters, or even emergency medical service personnel.

A theoretical model for tactical periodisation

The goal of a successful tactical strength and conditioning programme is to find ways of building robust athletes while creatively navigating the inherent difficulties of the tactical environment. These include deployment schedules, off-site training requirements, permanent changes of assignment, frequent trips across several time zones, and austere operational conditions. These types of factors highlight the biggest differences between a tactical programme and an athletic programme.

Several strategies exist to adapt to these challenges. At the micro level, it really comes down to creative programming and the ability to think and manoeuvre quickly in response to changing circumstances. Combining strength and rehabilitative movements into supersets or training circuits, for example, allows athletes to address both performance and preventative components in a timely manner (7, 13).

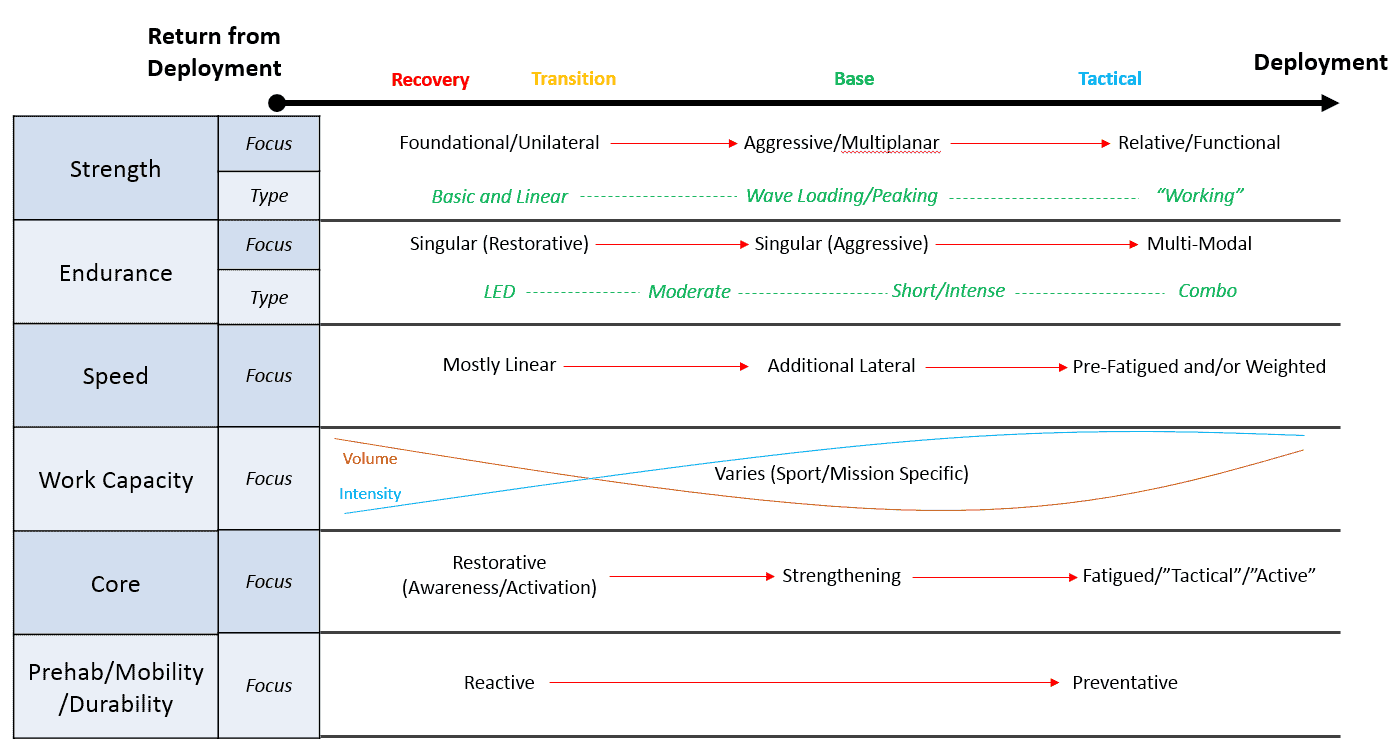

At the macro level, a more sports-esque model of periodisation can be applied, assuming that some consistency is achievable between deployments or larger off-site training iterations. The chart below is largely theoretical; however, the principles are prime examples of the flexibility required when overlaying traditional periodisation onto a tactical model (Figure 1).

As the athlete moves through the cycle from one deployment to the next, the emphasis in all aspects of training (rehabilitative, performance-based, etc.) shifts from recovery to transition, to base building to tactical (i.e. sport-specific), and then finally to deployment.

Recovery

The initial phase of training following deployment is focused on re-establishing baselines and rebuilding the operator. Depending on the nature of the deployment, injuries can range from simple overuse issues to missing limbs, and as such, early-stage reintroduction into the training pipeline can pay huge dividends throughout an athlete’s career.

During the recovery phase, strength and endurance progressions are kept relatively basic and linear, metabolic conditioning (i.e. work capacity) tends to be higher volume at lower intensities, and any sort of rehabilitative interventions are reactive in the sense that specialists are usually responding to injuries sustained on the previous deployment. The overall emphasis across all stimuli is base building.

Transition

The transition phase is a short iteration in which the focus shifts from addressing the previous deployment to preparing for the next one. The training itself may not be much different than the cycles administered during the recovery phase, however, the mindset shift is clear in that the emphasis for all future training is on the upcoming mission set.

Base

The base phase of training is by far the largest and most difficult to navigate for tactical strength and conditioning specialists. With the high operational tempo of tactical athletes, it is imperative that the specialist navigates the fine line between simply maintaining and actively improving performance. Whenever possible, a certain percentage of the programming should start to reflect the nature of the upcoming deployment. This is because the training required for a mountainous deployment will look very different than the training required for, say, a desert operation.

Base phase programming typically consists of shorter, more aggressive cycles interspersed between longer maintenance cycles employed when tactical athletes are offsite or away from any sort of normal training environment. Strength and endurance progressions tend to be shorter, with intensity playing a key role over volume simply because the time available to train is often brief.

In terms of more ‘tactical’ training (e.g. speed, agility, and work capacity), more complex movements and/or circuits are introduced, albeit still in an unweighted and non-fatigued state. Despite the name of the phase, the overall emphasis shifts from base building to deployment preparation, with an increased focus on what could be considered as sport-specific training.

Tactical

The final phase of training prior to the actual deployment is where programming becomes almost exclusively sport-specific. If the performance team as a whole has been effective, operators should be fully recovered from any injuries sustained on the previous deployment.

In general, as teams move closer to deployments, the operational tempo (or time spent off-site) slows down slightly to allow for more time at their home station. This is an advantage for the tactical strength and conditioning specialist, as the nature of the training itself must become more complex to reflect the inherent complexity of the upcoming deployment. Volume and intensity should both be high, although the focus should remain on generating functional (i.e. working) fitness.

An especially important component of the tactical phase of training is the introduction of weighted and pre-fatigued movements. In many cases, this can be as simple as prescribing the use of weighted vests for certain movements, although more complicated pre-fatiguing interventions such as Litvinov Conversions and Mixed Modal Aerobic protocols are also important. This is also a good time to introduce more exotic concepts such as range fitness (i.e. incorporating firearms into training), timed target acquisition within metabolic circuits, fatigued battlefield medicine procedures, etc.

Deployment

All of the training phases described above should seamlessly integrate to transition a tactical athlete from one ‘season’ to the next. When programmed efficiently, the training will easily complement whatever job-specific tasks are required by the athlete in such a way that injuries are avoided, fitness levels are maintained, and performance as a whole is steadily improved upon throughout the athlete’s career.

Why is tactical strength and conditioning important?

The United States has been involved in global conflict for 16 continuous years (3, 11, 14). The nature of today’s fight requires that soldiers are able to withstand multiple 4- to 18-month deployment cycles interspersed with home-station periods of rest, recovery, re-training, and then subsequent re-deployments. In 2016 alone, US Special Operations Command (SOCOM) had troops deployed in 138 different countries, nearly 70 % of the world’s nations, averaging 1-3 months at home for every month they were deployed (4).

Not only is tactical strength and conditioning important for physically preparing the athlete for the high-operational tempo, but it also plays a role in protecting the athlete from themselves (2). Musculoskeletal injury frequencies hover around 25 injuries per 100 operators per year for total injuries and around 19 injuries per 100 subjects per year for preventable injuries (12). Of those injuries classified as preventable, 75 % occur during some form of physical training (command organised, non-command-organised, or unknown) (12).

With such a high frequency of injuries tied to ineffective physical training, it stands to reason that a professionally organised performance programme can play a significant role in maintaining the health and well-being of tactical athletes.

What is the future of tactical strength and conditioning?

As with the unpredictable nature of warfare, it is somewhat difficult to gauge the future of tactical strength and conditioning. That being said, all signs point to a growing effort within the US Government to expand the initiatives currently in place. As of 2017 the initial SOCOM POTFF 5-year contract worth $475 million (USD) will be renewed for an additional eight years, with further extensions likely. With increased funding and personnel comes increased improvements across all elements of tactical strength and conditioning.

Special attention is being paid to wearable technologies, third-party software platforms, nutritional supplementation, and high-level recovery methods (5, 8). Another major area of emphasis is the accuracy and effectiveness of current physical fitness testing protocols (1, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10). In nearly every case, these tests reflect outdated training methodologies and an overemphasis on muscular endurance and aerobic fitness. As the battlespace evolves and demands more anaerobic qualities from tactical athletes, military fitness tests will likely be redesigned to include load-carrying components and more occupation-specific tasks. Future tests should not only capture performance data, but also training effectiveness, injury status, and the ability of operators to return to duty after being taken off status (10).

Another glaring weakness within tactical performance programmes is the lack of emphasis placed on nutritional support (5). Hydration has always played an important role in tactical research and implementation, however, very few initiatives have successfully been put into place to cater to the unique nutritional demands of tactical athletes (5). As the importance of sound nutritional principles becomes clear to tactical athletes, and as new technologies emerge to make the acquisition of nutritional patterns more accessible, it is likely that this area of performance will garner more support.

What future research is needed with tactical strength and conditioning?

International organisations and leadership summits in various areas of tactical performance have determined a few key areas for future research. In order of importance, the top five topics are as follows (5):

- Physical demands in operational environments.

- Measuring physical performance/fitness.

- Musculoskeletal injury mitigation programmes.

- Physical employment standards.

- Physical strength-training programmes.

In addition to performance-related topics, emphasis should also be placed on nutrition and supplementation, sleep, gender integration into special operations, and perhaps most importantly, various areas of psychology as it relates to mental fitness (10).

Conclusion

As the demand for high-level operators increases around the globe, and as the resulting high-operational tempo takes its toll on tactical athletes both mentally and physically, the role of tactical strength and conditioning will only increase.

For centuries, the importance of the human element to the battlefield has been emphasised, however, actionable intervention into the health and performance of the tactical athlete has only gained significant traction in recent years. New and evolving methods of periodisation, as well as the innovative application of more traditional approaches, will inevitably lead to new findings and increased knowledge relating to the training of tactical athletes.

As more funding becomes available for performance programmes and the specialists involved in delivering them, additional research will begin to identify the most effective ways to deliver the services that tactical athletes need (i.e. prevention, treatment, sustainment, and enhancement).

- Bear, R., Sanders, M., Pompili, J., Stucky, L., Walters, A., Simmons, J., Terrell, D., Lacanilao, P., Eagle, S., Grier, T., DeGroot, M., Lovalekar, M., Nindl, B., Kane, C. and Depenbrock, L. (2016). Development of the Tactical Human Optimization, Rapid Rehabilitation, and Reconditioning Program Military Operator Readiness Assessment for the Special Forces Operator. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 38(6), pp.55-60. http://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/Abstract/2016/12000/Development_of_the_Tactical_Human_Optimization%2C.6.aspx

- Blacker, S., Wilkinson, D., Bilzon, J. and Rayson, M. (2008). Risk Factors for Training Injuries among British Army Recruits. Military Medicine, 173(3), pp.278-286. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18419031

- Cahn, D. (2017). Special Ops General: Rate of Deployment ‘Unsustainable’. [Blog] Stars and Stripes. Available at: http://www.military.com/daily-news/2017/05/05/special-ops-general-rate-of-deployment-unsustainable.html [Accessed 18 Sep. 2017].

- Deuster, P. and OʼConnor, F. (2015). Human Performance Optimization: Culture Change and Paradigm Shift. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29, pp.S52-S56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26506199

- Hydren, J. and Zambraski, E. (2015). International Research Consensus: Identifying Military Research Priorities and Gaps. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29, pp.S24-S27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26506193

- Jones, B. and Hauschild, V. (2015). Physical Training, Fitness, and Injuries: Lessons Learned from Military Studies. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29, pp.S57-S64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26506200

- Knapik, J., Darakjy, S., Scott, S., Hauret, K., Canada, S., Marin, R., Rieger, W. and Jones, B. (2005). Evaluation of a Standardized Physical Training Program for Basic Combat Training. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(2), p.246. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15903357

- Nindl, B. (2015). Physical Training Strategies for Military Womenʼs Performance Optimization in Combat-Centric Occupations. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29, pp.S101-S106. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26506171

- Nindl, B., Alvar, B., R. Dudley, J., Favre, M., Martin, G., Sharp, M., Warr, B., Stephenson, M. and Kraemer, W. (2015). Executive Summary From the National Strength and Conditioning Associationʼs Second Blue Ribbon Panel on Military Physical Readiness. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29, pp.S216-S220. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26506191

- Nindl, B., Jaffin, D., Dretsch, M., Cheuvront, S., Wesensten, N., Kent, M., Grunberg, N., Pierce, J., Barry, E., Scott, J., Young, A., OʼConnor, F. and Deuster, P. (2015). Human Performance Optimization Metrics: Consensus Findings, Gaps, and Recommendations for Future Research. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29, pp.S221-S245. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26506192

- Sears, D. (2017). Building Resiliency: How Special Operators and Their Families are Bouncing Back. [Blog] Military Officers Association of America. Available at: http://www.moaa.org/POTFF/ [Accessed 19 Sep. 2017].

- Sell, T., Abt, J., Lovalekar, M., Bozich, T., Benson, P., Morgan, J. and Lephart, S. (2014). Injury Epidemiology of US Army Special Operations Forces. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 46, p.759. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25269128

- Solberg, P., Paulsen, G., Slaathaug, O., Skare, M., Wood, D., Huls, S. and Raastad, T. (2015). Development and Implementation of a New Physical Training Concept in the Norwegian Navy Special Operations Command. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29, pp.S204-S210. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26506189

- Turse, N. (2017). American Special Operations Forces Are Deployed to 70 Percent of the World’s Countries. [Blog] The Nation. Available at: https://www.thenation.com/article/american-special-forces-are-deployed-to-70-percent-of-the-worlds-countries/ [Accessed 18 Sep. 2017].

- Beam, T. and Sparacino, L. (2003). Military medical ethics. Falls Church, Va.: Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army.